In September, I spent three weeks in Newfoundland, Canada working on world class Ediacaran fossil surfaces with Emily Mitchell, Charlotte Kenchington and Lucy Roberts. After eight hours of travelling, our bright red truck full of precision equipment, people and food arrived in the town of Portugal Cove South. We settled into ‘The Green House’, where we would be staying, and promptly collapsed in bed.

This fieldwork was the final field season of a three year project to map all of the oldest deep-water Ediacaran fossil communities across Newfoundland, Canada and Charnwood Forest, UK. These fossil communities consist of thousands of immobile organisms preserved in-situ so that the fossil surfaces are a near-census of Ediacaran life. Therefore, the fossil positions encapsulate their life-history of the organisms: how they reproduced and interacted with each other and their local environment.

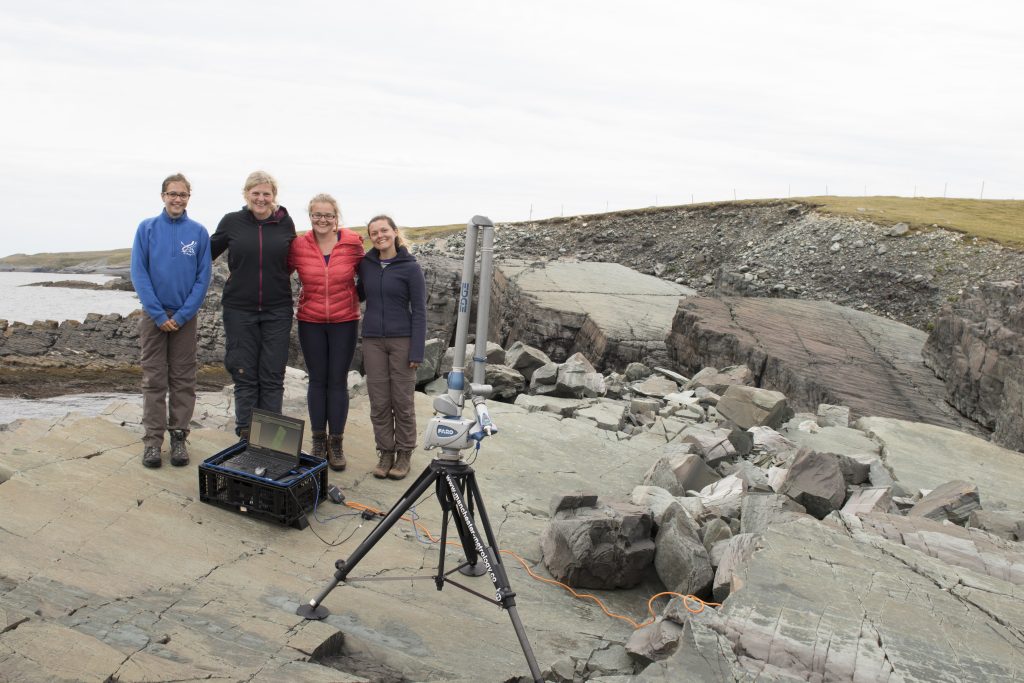

The two main aims for this trip were high resolution laser scanning and photomapping the surfaces. The sensitivity of the scanner meant we couldn’t work in fog or rain, the main weather conditions on the Avalon peninsular. When the forecast was good, we worked dawn ‘til dusk to maximise field time, meaning we were up at 6am on day one, trekking out to the first surface, ‘Pizzeria’, with 150kg of kit by 8am. It is called ‘Pizzeria’ due to the abundance of ivesheadiomorph fossils on the surface, that resemble pizzas, which are thought to be the decaying remains of other organisms.

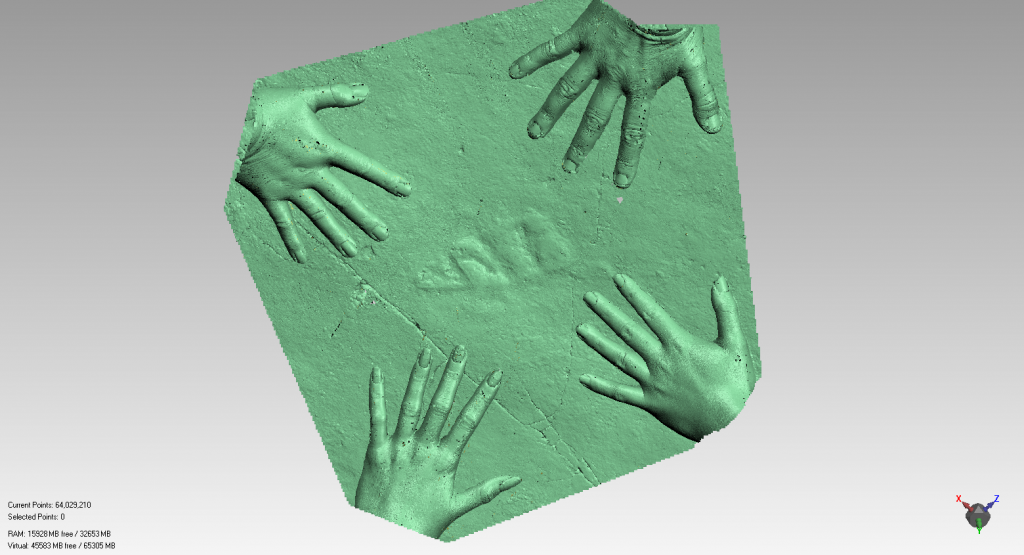

The fossils surfaces were formed when the ocean floor was buried under ash flows from volcanic eruptions meaning the organisms were preserved in life positions with exceptional detail. The fossils are low relief and have no colour difference from the surrounding bedrock meaning they are difficult to see unless the light is at a low angle to the surface.

When we arrived at Pizzeria the light was ideal, Charlotte and I set about photomapping; taking overlapping photographs of the surface covering it systematically. We took close ups of the more detailed or unusual fossils. Meanwhile, Emily and Lucy set up the Laser scanner and began scanning the surface; slowly passing the scanner head over the rock to generate a 3D representation of the surface with 50μm resolution, covering about 1m2 per hour. We had to shade the scanner because the sun reduces the resolution of the scans. After three days Pizzeria was fully scanned and photomapped.

On Day Four we moved the kit to D & E surfaces of Mistaken Point with the help of the Cape Race lighthouse keeper, Cliff and his ATV. Emily and I photographed individual fossils on E surface, while Charlotte and Lucy photomapped G surface. This outcrop of G surface has a near vertical dip and plunges into the ocean, so Charlotte used a 400mm camera lens and perched on a rock across the water from G.

D & E surfaces have finer preservation than Pizzeria, due to the smaller grain size of the bedrock, and a different community composition consisting of predominantly Fractofusus as well as various rangeomorphs, Charniodiscus, Bradgatia and Thectardis. We spent a week scanning D surface and the smaller Mistaken Point surfaces, including a Hapsidophyllas on F surface and a flatter outcrop of G surface.

After nine caffeine fuelled days of glorious sunshine we needed a break; the fog and rain agreed, becoming gloomier for the rest of the time. While we got a few days scanning Pigeon Cove, which had mainly Thectardis and ivesheadiomorphs, many of the rainy days were spent exploring other surfaces in the Mistaken Point reserve and helping Cliff at the lighthouse eat his delicious cakes. There was plenty of opportunity to admire the beautiful scenery and wildlife, including Bald Eagles, Seals, Moose and a charming Fox named Tripod.

We spent the final few days in Bonavista, exploring and photomapping the surfaces. We stayed in the recently renovated masters house, where the undergraduate mapping students had been, and were looked after by Edith and Nev Samson and their kitten, Sophie (named after recent visitor and current Part III student Sophie Baldwin).

On our way back to St John’s we stopped off at the Spaniard’s Bay surface to take photographs. This surface is especially breathtaking because of the ‘3D preservation’ of the fronds; they have a much higher relief than most of the other fossils in Newfoundland.

The final thing to do was to get Lucy and I ‘screeched in’ in St John’s to become honorary Newfoundlanders. We kissed a cod, drank some screech, and learnt some local sayings before the tiring overnight flight back to the UK.

Sasha Dennis Part II student

Fabulous place. Globally Special. Interesting article. Txs

So fascinating! Best of success to your research!

Very interesting. Love your writing style!