While many of my friends spent their summer vacation swanning off to remote corners of the world for some well-deserved rest and relaxation, I decided that it would be fun to spend August doing some lab work in Cambridge—I was actually pleasantly surprised.

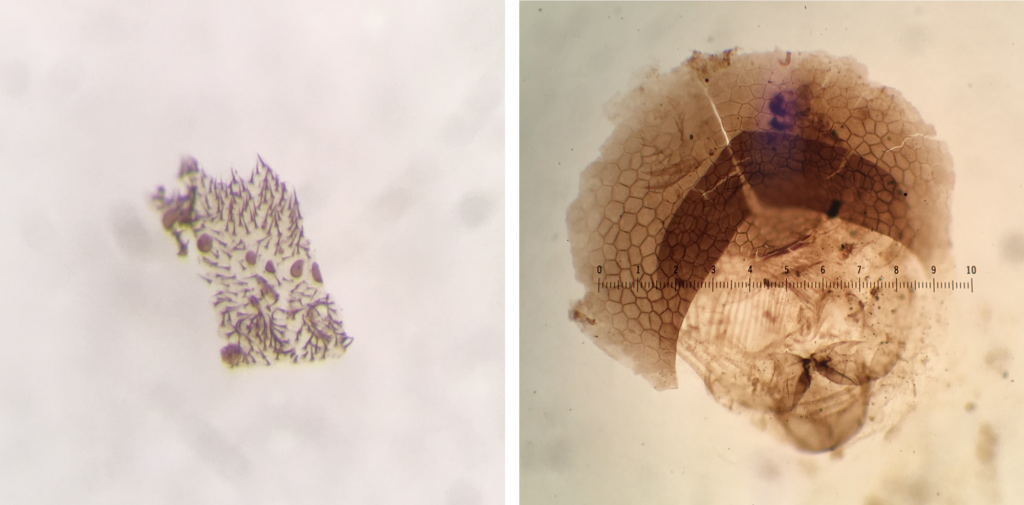

I was working for Nick Butterfield on some lake sediments from Idaho, which were deposited around 10 million years ago. These Miocene lakes would have contained pretty much all the life that you’d expect to find in a lake: fish, midges, their larvae and pupae, flies, crustaceans, plant matter, and of course, fungi. The sediments contain exceptionally well preserved fossils of all the organisms listed above, so my job was simple: to get the best fossils out of the rocks and mount them onto slides for examination. The process for fossil extraction is surprisingly low-tech! First, the rock is dissolved in HF (don’t try this at home), then the sediment is suspended in water and put in a Petri dish, so I can then spend many happy hours looking at it under a microscope to find interesting looking fossils!

The job started out pretty simply: a day looking at previously collected specimens so I could get my eye in. Then began the month of picking out my own fossils! Everyone who has done picking before (whether it be fossils, olivine crystals, or forams) will know that ‘picking’ days can seem very long—I recommend podcasts to get you through! The work can be extremely fiddly, as the fossils are very delicate and cannot be left to dry out until the last possible moment. Therefore, once the fossils have been pipetted onto the slide, you have work quickly and carefully. Using a fine filament, the aim is to lay them out as flat as possible (they have an annoying habit of folding up onto themselves) and then remove the water droplet without moving the fossil from the beautiful position you’ve just forced it to adopt—this process required a level of zen that I have never before needed in my life.

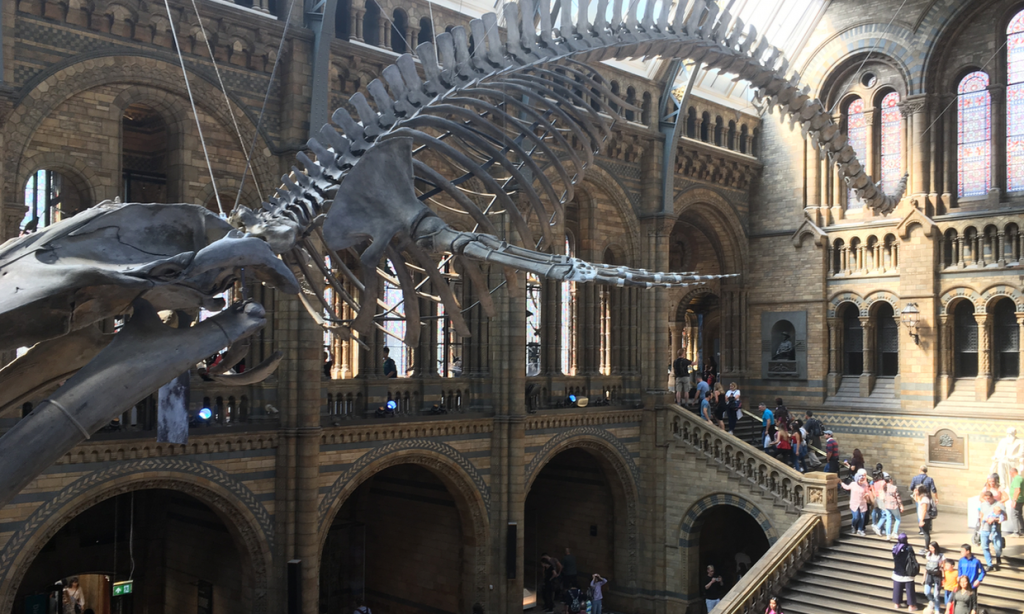

At one point in my fossil searching, I came across a creature that looked very bizarre and not unlike something from ‘Stranger Things’ (see image below). I was starting to think that the prospect of going swimming in a Miocene lake was a bad idea, when I was informed that the spiky creature was not actually a fossil, but rather something that had floated in through the window and into my Petri dish. As such, you and I now have to live with the knowledge that these demon critters are just drifting around in the air—don’t worry though, they’re very small!

One very exciting part of the project involved putting some of the specimens under the scanning electron microscope (SEM) to observe their fine details. Although this imaging technique involves more fiddly prep work, the results were very much worth it: we were able to see beautiful fine filaments coming off the midge larvae that are not visible under an optical microscope. Playing with the SEM is very fun, and Iris Buisman (Lab Technical Officer) is very lovely and helpful when you don’t know what to do!

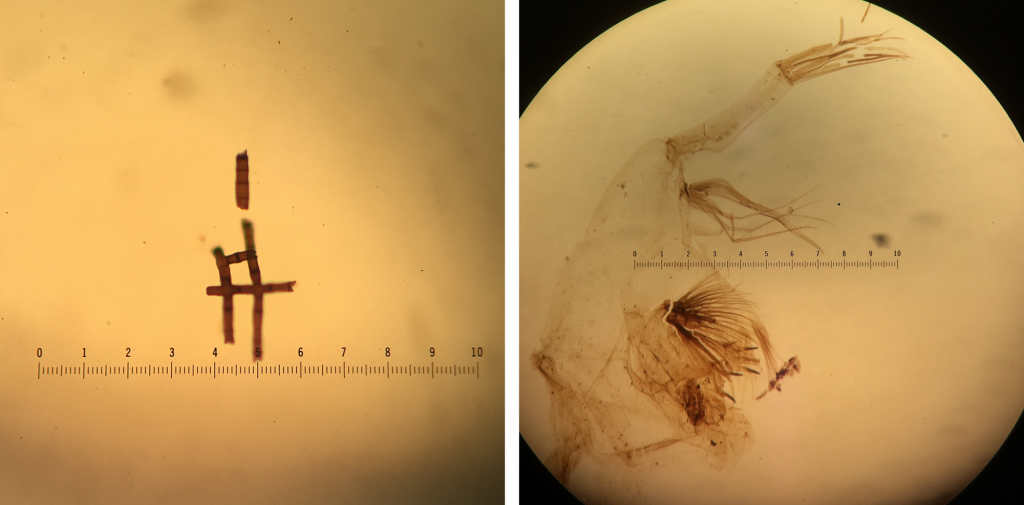

Overall, I would recommend doing a summer project in the Department of Earth Sciences. I had a really fun time and hopefully produced some useful specimens for future work! Plus, the experience opened the door to some really fun opportunities in the Department: going to coffee time, which is especially enjoyable when lecturers bring their dogs; going on palaeontology pub trips, which in summer means swapping traditional Earth Sciences beer for Pimms; and being in Cambridge makes it very easy to take day trips to London to visit the Natural History Museum!