The roles of museum curators and archivists are often shrouded in mystery – what do they get up to behind the scenes? In this post I lift the lid on the profession and give you an insight into my job as Sedgwick Museum’s Collections Assistant for the intriguingly named, Moving a Mountain project. But first, I’ll start at the beginning – how I first got hooked on museum collections.

Museums and other historic collections have always fascinated me. I remember visiting historic houses and museums as a child, and at school always had a fondness for history – so studying archaeology at university was an obvious choice. It was through my studies, work experience and volunteering opportunities that I discovered what I loved most about museums: being up close and personal with the collections and quite literally getting my hands on history.

My first step into museum work was actually through the National Trust, where I started working as a Conservation Assistant and then progressed to House Steward. At the National Trust I looked after the house collections – carrying out daily cleaning as well as planning and executing more in depth care routines.

Sorting through the collections as part of the Moving a Mountain project

There was a part of me that wanted to see what it was like to work in a museum, and how that would be different to a historic house. I was still early in my career (and still am in fact), so I decided to take the risk on a 6-month contract as a Collections Technician at the National Museum of Scotland – possibly my favourite museum to visit (except the Sedgwick of course!). That job expanded my knowledge of collections from mostly furniture and ceramics to ethnographic, scientific, zoological, and transport collections, to name a few.

My current role as Collections Assistant for the Moving a Mountain project, involves relocating the Sedgwick Museum’s collections that are currently in storage at the Atlas building to the new geological store in the Forbes building. This means moving approximately 12,000 drawers of rock specimens, weighing around 150 tonnes in total! It’s a mammoth task, and there are all sorts of treasures in the collections. Many of them are of scientific importance, including the Harker Petrology collection, as well as those used for teaching and exams within the Earth Sciences Department.

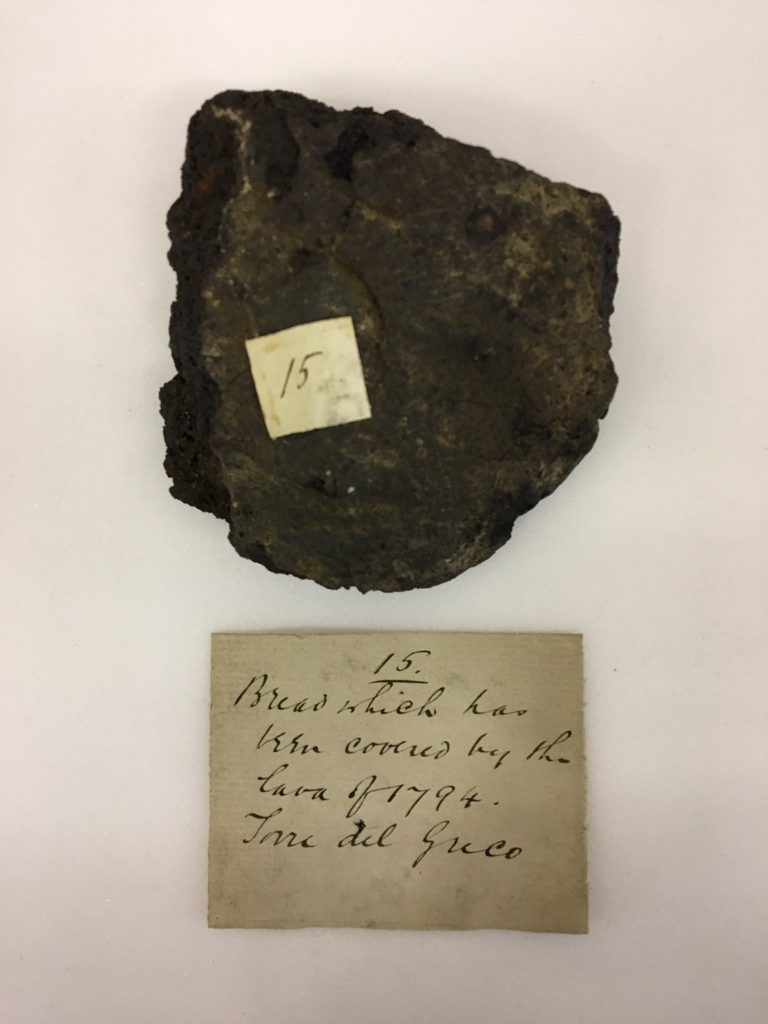

As someone with only a basic knowledge of geology it’s been a very enlightening collection to work with. For me, the most interesting parts of the collection are those with interesting historical connections. For example, this piece of bread that was preserved in lava from the 1794 eruption of Vesuvius. I also like to think about where in the world the rock specimens have come from. I love travelling, and in a time where going abroad is restricted something as simple as a rock in my hand can transport me to new and exotic corners of the world. One find that comes to mind is the sand collected from the shores of the Ross Sea during Ernest Shackleton’s 1907 Antarctic expedition (a favourite I share with our volunteers, who discussed it here). To think how far, in time and distance, this collection of geological specimens has come, and the small part I get to play in looking after it is a special feeling that I often take for granted.

Moving all these rocks is no small feat – so why are we moving them? Rocks, like all historic collections, degrade if they are not stored carefully. Fluctuating temperature and humidity can cause decay, such as pyrite oxidation, and also damage the labels and storage. The new store has a controlled, stable environment which will ensure the long term preservation of the collections.

What does moving such a large collection involve? We split the process into different stages: triaging the drawers for any potentially hazardous material, documenting the contents of each drawer, cleaning, packing and digitising each one, then transporting them and putting them in the new racking. On a ‘typical day’ (although is that a thing in COVID times?) I would be mainly working on either cataloguing the drawers, logging the condition and weight of the rocks, or cleaning, packing and digitising them. We clean each drawer so we’re not bringing any dust or other dirt into the new store, and whilst the drawer is emptied for cleaning a birds-eye view image is taken of the specimens. Before the first lockdown, I was also supervising a team of volunteers who were helping out with these tasks. Although they’re currently unable to assist on the project, I’ve still been keeping in touch with them and have even started a monthly newsletter for all the museums volunteers.

I’ve also really enjoyed all the new pieces of equipment I’ve had the chance to use. Not only have I got to improve my skills with a pallet truck (something I weirdly enjoy for some reason), but I’ve been fortunate enough to help move some of the museums largest fossils with our stacker. Looking down from our Genie lift, which we use when filling the racking, I can get a whole new view on the store.

Working at the Sedgwick has been a great opportunity to explore a new area of the museums sector and be part of moving such an impressive and valuable collection. Although geology is unfamiliar to me, I’ve learned just how similar it can be to subjects more in my comfort zone, like archaeology (and not just because of the amount of dirt that’s involved!). These collections are used to interpret the Earth’s history, as well as our impact on it, and that is what has always drawn me to museums.

If you’d like more of an insight into the world of museums, and to keep up to date with the collections move, then give the museum’s social media channels a follow (Twitter/Instagram: @SedgwickMuseum, Facebook: Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences).