The time sequence of building stone use in Cambridge shows the competing influences of function, fashion and finance in the city’s historic fabric. Now natural stone is poised for a resurgence because of its strength, durability and low embodied carbon.

Cambridge buildings display one of the UK’s best records of historic stone use. Never systematically researched, it has remained an underused resource for educators, historians and architects.

So, in 2019, Euan Furness and I surveyed all Cambridge buildings with significant exterior stone[1]. We identified the types of stone in each building and assigned a date and a rough volume to each of the thousand or so construction or repair projects involving stone.

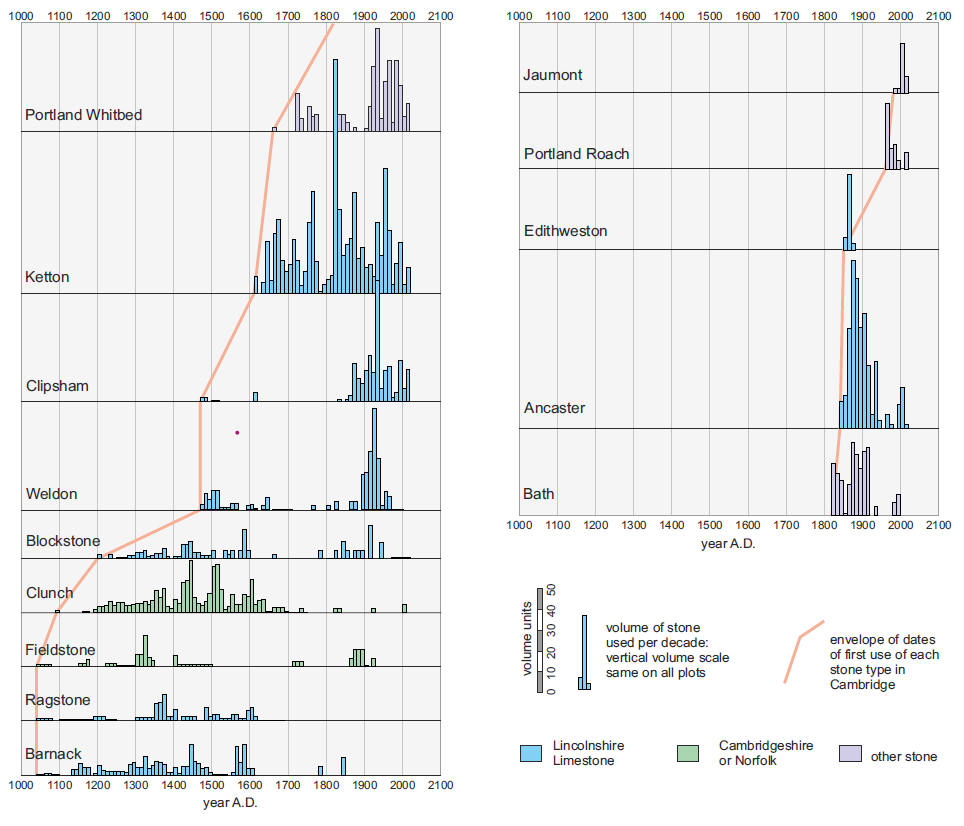

We identified 23 main stone types, almost all (94%) limestone. Two-thirds of that limestone comes from the Middle Jurassic Lincolnshire Limestone Formation that extends from Lincoln southward to Corby. Nine main quarry areas have supplied stone to Cambridge, particularly Ketton (35%). Ancaster (18%), Clipsham (10%) and Weldon (9%).

The bar charts below show the pattern of use of each stone, with each bar showing the volume used in one decade.

These charts – ordered by the first use date of each stone – reflect key historical influences, for instance:

- Before the 15th century, low quality stone came either from local Cretaceous Clunch (hard Chalk) or from locally harvested fieldstone. High quality stone was imported from Barnack, 60 kilometres away in the Jurassic limestone belt.

- After the Black Death (1349), the supply of fieldstone declined due to the decreased area of arable farming.

- Barnack stone supply declined after 1460 as the quarries were worked out. Recycled sources arose from demolished monasteries after their dissolution in 1536-41.

- White Portland limestone became fashionable in the 18th century, despite the long coastal transport route from the south coast of England.

- In 1847, the extension of the railway network to Cambridge increased the variety of distant UK stone that was used in Cambridge, notably from Bath in southwest England and from Ancaster, the most northerly of the good Lincolnshire limestones.

The choice of building stone was influenced by three factors: a) its intended function; for instance, medieval Clunch was best for carving but Barnack was more weather resistant; b) the prevailing fashion; c) the finance available for the project. The cost of medieval stone doubled when transported only ten miles overland from the quarry. Even if stone such as Barnack was moved by inland waterways at about a fifth of the overland cost, the economics still favoured more local stone. The artificially low cost of fossil fuels through the 20th century has decreased the global pressure to use local construction materials; but this is set to change.

But what modern relevance is a study of historic building stone? It certainly helps architects to identify stone in restoration projects and to source alternatives. More importantly, a historical study shows the range of stone available for new-build projects, and the Cambridge buildings where their durability can be assessed after centuries of natural weathering.

Surprisingly perhaps, natural stone is regaining favour as a construction material, not just because of its strength, durability and beauty but because of its low embodied carbon[3]. Stone does not have to be fired like brick or kilned like cement or dried timber. Stone for walling or dressings is simply cut to shape. Long stone beams can be created by joining blocks with glue and a tensioned steel cable.

So, building stone – available as it is in large volumes – should play an increasing role in future construction. This trend will need geologists to find and monitor resources. Increasing fuel costs will likely mean more pressure to use local stone. Maybe the inner skins of Cambridge buildings will once again be made of blocks of local Clunch, just as in medieval Cambridge.

Want to know what stone your college is made of? Consult Nigel Woodcock’s brief guide, available to download here.

References:

[1] N. H. Woodcock and E. N. Furness, ‘Quantifying the history of building stone use in a heritage city; Cambridge, UK, 1040-2020’, Geoheritage, vol. 13, p. 12, 2021, doi: https://bit.ly/3WGHQqr

[2] N. Woodcock, ‘Building stones of Cambridge colleges’, Cambridge, 2023. https://bit.ly/4fZv4tN

[3] A. Klemm and D. Wiggins, ‘Sustainability of natural stone as a construction material’, in Sustainability of construction materials, Elsevier, 2016, pp. 283–308. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://bit.ly/4jqWPOW