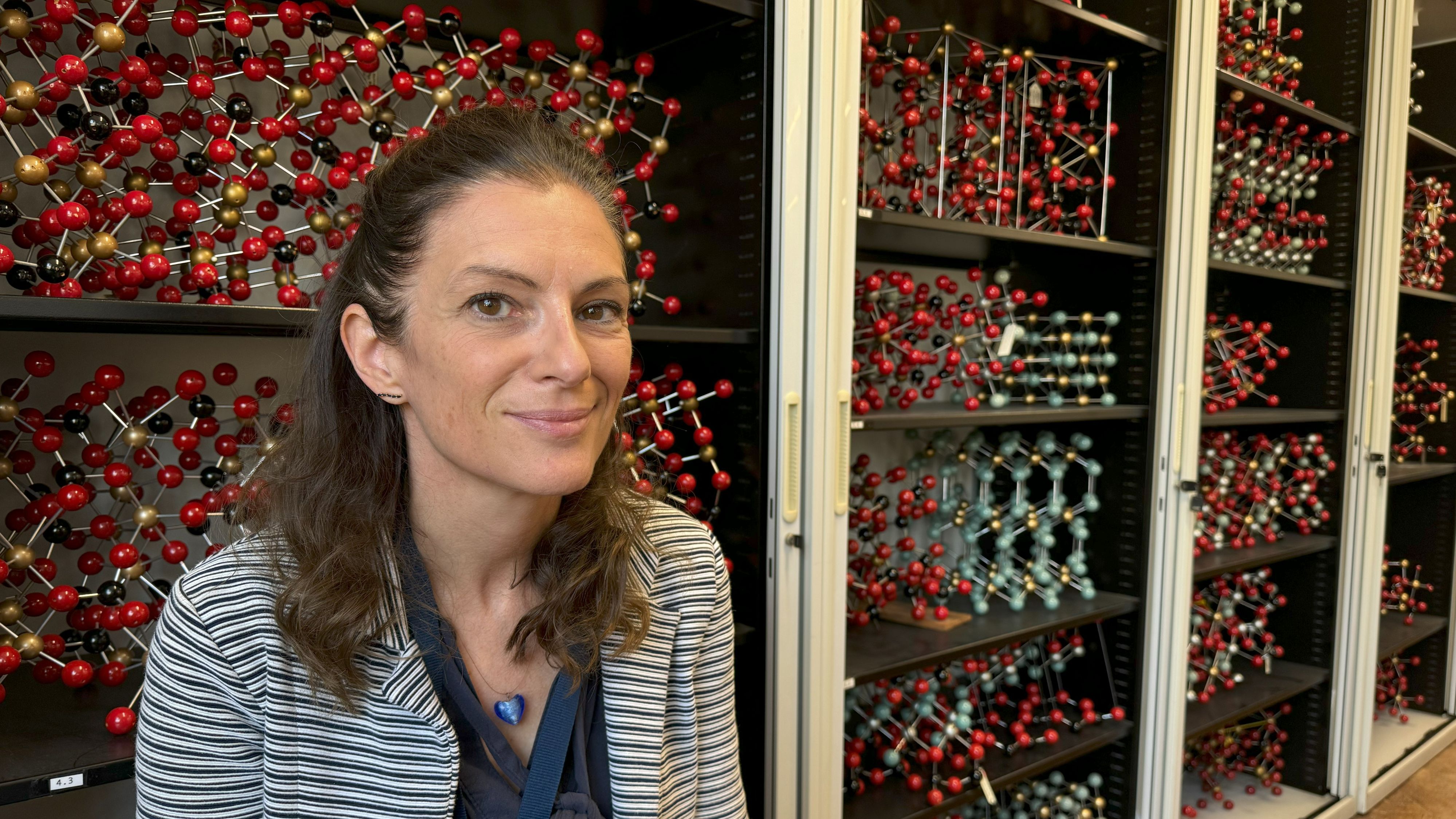

Marie Edmonds, Professor of Volcanology and Petrology, was both an undergraduate and postgraduate in Cambridge from 1994-2001 and has been a lecturer in the Department of Earth Sciences since 2006. Marie reflects on her career and new role as Head of Department with Erin Martin-Jones.

One volcanic eruption kick-started your career as a volcanologist?

Volcanoes weren’t a stand-out interest as a child. But, as a Natural Sciences undergraduate, volcanology really clicked for me. The subject suited my broad interests. David Pyle was my lecturer, and I stayed on at Cambridge for a PhD with him. I didn’t spend much of my time in Cambridge though—I was lured away by a volcano in the Caribbean!

Soufrière Hills, in Montserrat, had been erupting for two years when I started my PhD in 1997. The eruption was making world news, and, because Montserrat is a British Overseas Territory, British volcanologists were flocking there to assist with the monitoring effort.

Montserrat wasn’t in my original PhD design; I insisted on going there! My interest was in the volcanic gases and the melt inclusions trapped inside crystals as the magma rose. Some extremely useful insights came from my work, showing that sulphurous volcanic gases originate deep in the crust rather than being formed nearer the surface as had been thought.

More broadly, the eruption was decisive in developing UK volcanology. Over the two decades that the volcano was active, countless papers came out led by British volcanologists. We learnt a huge amount about long-lived, start-stop eruptions, and managing their complex hazards.

You’ve worked at several volcano observatories?

Following my PhD, I continued to work at the Montserrat Observatory as a junior volcanologist for the BGS. We installed UV spectrometers that scanned the volcanic plume and sent gas measurements back to the observatory every few minutes. That was a world-first; the instruments were fully telemetered and ran autonomously on solar power. I remember when we initially got the system installed—we could sit in our offices and watch all this data streaming in, it was a powerful moment! (Today the same remote gas monitoring methods are in operation at perhaps 35 volcanoes around the world).

After that spell with the BGS, I secured a USGS Mendenhall Fellowship working alongside Terry Gerlach—a giant in the field of gas geochemistry—at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. I was in a privileged position: Hawaiʻi is known as the laboratory volcano because you can test new instruments there. I could collect data day in day out, learning and developing ideas all the while. During that time, I was seconded to the Cascades Observatory when Mount St Helens erupted in 2004 and, in 2006, I visited the Alaskan Observatory to monitor the Augustine eruption.

These case study eruptions shaped my career. When I started out, I was a volcanologist focussed on volcanic degassing; how volcanic gases drive eruptions and in turn influence climate. But my experiences at different volcano observatories widened my horizons, and that’s when I started to think about the bigger picture questions of how volcanoes impact people and the environment.

What brought you back to Cambridge?

I came back to Cambridge as a lecturer and fellow at Queens’ in 2006. James Jackson invited me to Queens, something that changed my life at Cambridge. Having the college affiliation has meant so much to me, I think of it as a supportive extra family. The Department is also full of supportive people, many of whom I have known for a long time, including several who have been there for me since my undergraduate years.

I’m now in a place, as Head of Department, where I can give something back. I think of myself as one in a string of stewards; I am looking after the Department for the next five years and guiding it to the next place. It’s an exciting time where we can move forward together.

You have two children. How do you manage work and life?

Home-life is important, family is important. That balance is significant for every member of staff. There have been times where it’s been difficult for me, and I want to make it a priority to support those facing similar challenges.

From my own perspective, I’ve seen positive changes within academia. A couple of decades ago it was very much the women who were looking after the children. It was commonplace for academics not to discuss their family life at work, and the idea of leaving a meeting early to pick the kids up was frowned upon. But thankfully that’s different now — caring responsibilities are more balanced and flexible working is welcomed.

I really want our department to be a place where we can be content and, above all, accepting of each other. My philosophy is that everyone has their own circumstances and different needs, and we must be tolerant of how people want to work.

Read more about Marie’s research and her current SELVES project.