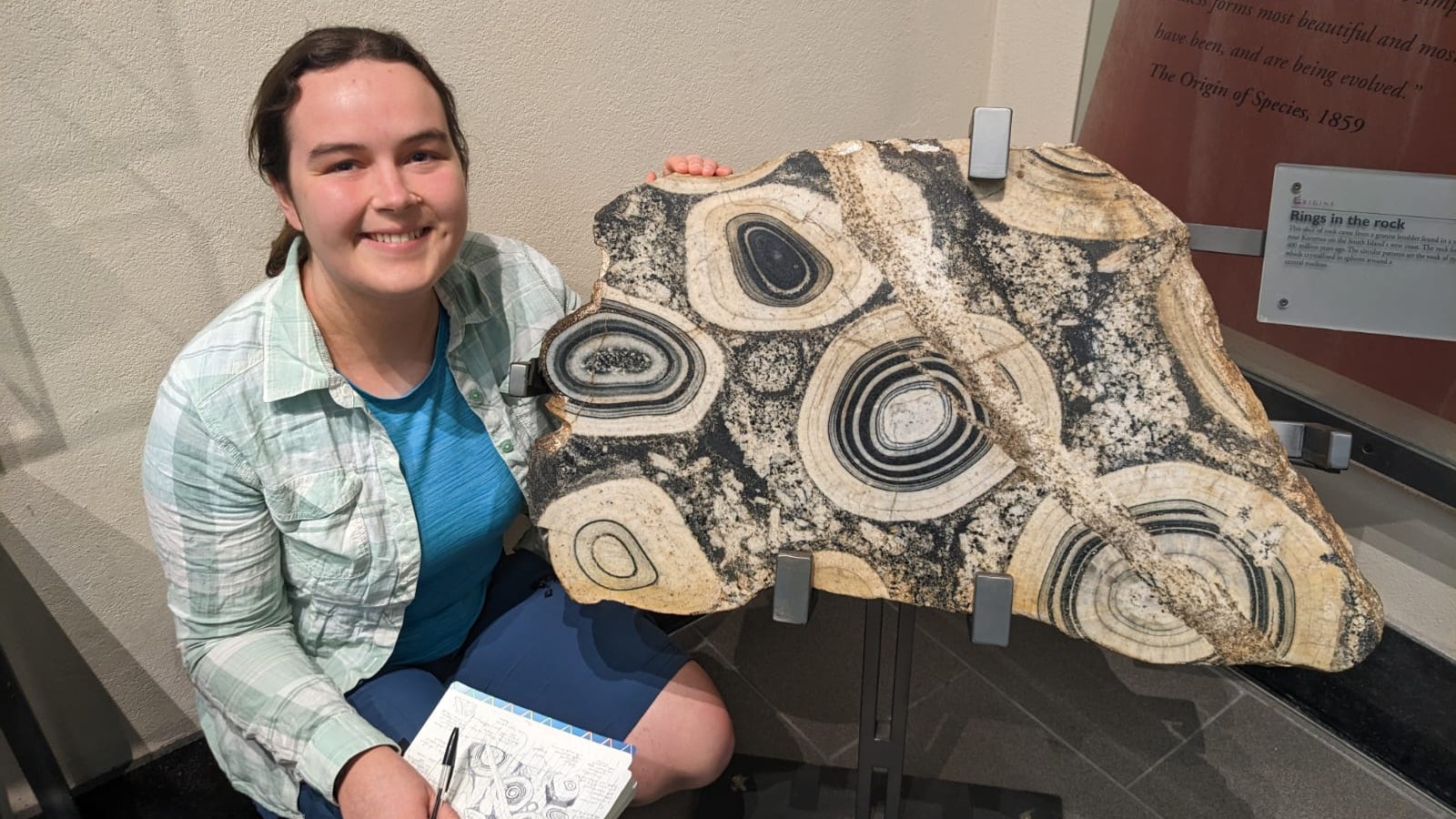

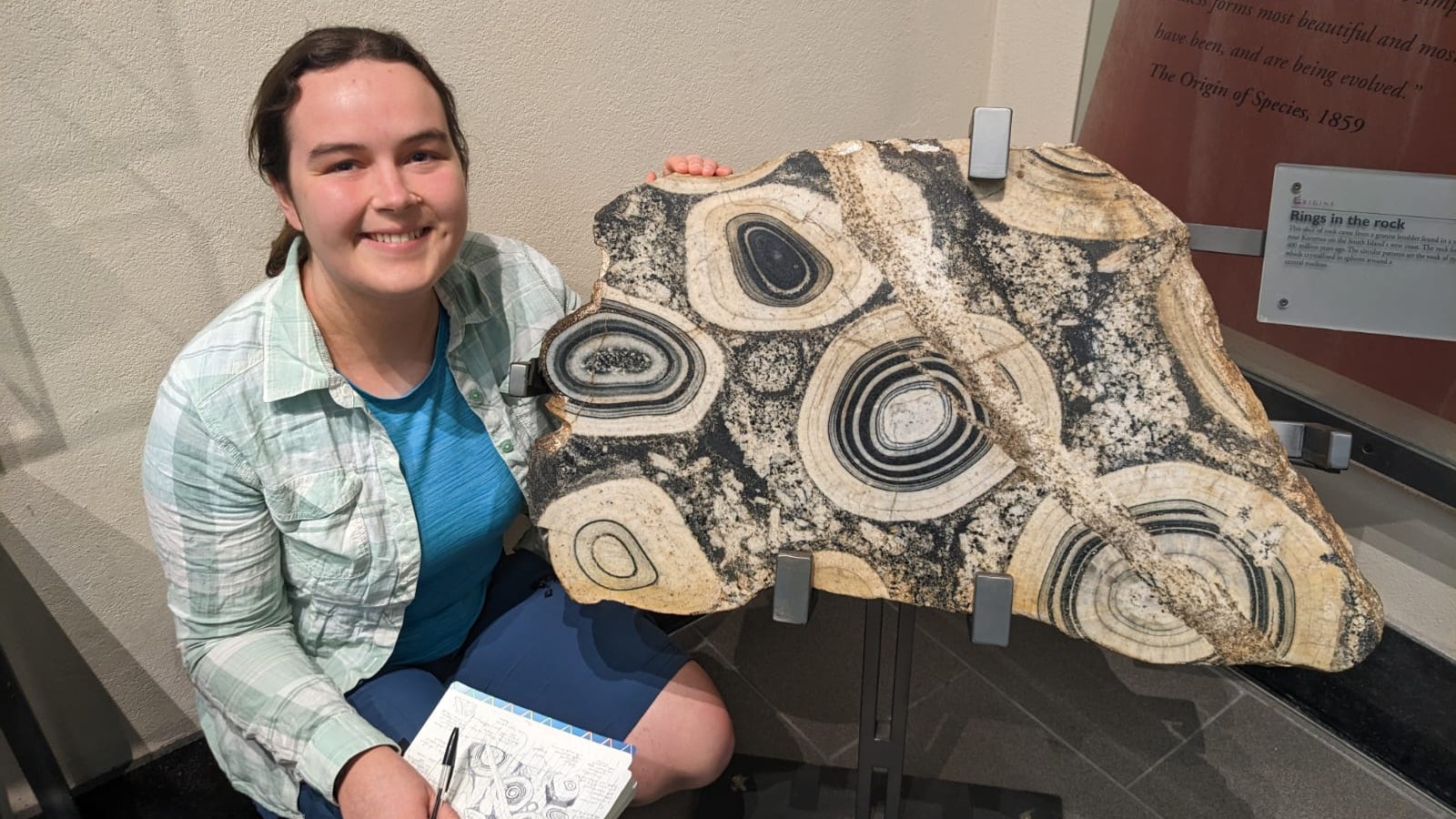

Once a year, a peculiar, polished slab of rock is hauled down from its home on a windowsill near the 1A lab and propped up on the lawn against a row of knees for the annual Sedgwick Club photo. The slab, with its striking black and white circular patterns, has featured in most annual photos in the past 60 years.

I first encountered the slab as a prospective PhD student in 2018 and was captivated. The rock is a spectacular orbicular granite. I had seen other museum examples of this orbicular granite, with tantalising signs saying, “scientists do not know how these rocks form…”. While we know that orbs crystallise in concentric layers from magma, the details are obscure. I decided that investigating orbs would make a great component of my research into igneous microstructure.

My initial exploration of museum collections was thrilling, with each dusty box holding the potential for revelations; I got to see hundreds of orbs, many of which were previously undescribed. The Sedgwick Museum records revealed that our photogenic slab hailed from New Zealand. I leapt at the opportunity to combine an international volcanology conference with a tour of New Zealand’s geological collections and a pilgrimage to the source of our department’s orbs.

Karamea is a small town nestled between the sea and remote forest in the north of South Island. The only access road winds its way precariously along the coastline. Karamea’s orbs have only been found in boulders, never in outcrop, and when I finally stood at the edge of the forest, I appreciated why!

The orbs emerge from rushing streams carved through lush, tangled rainforest that rises precipitously up the mountainside, thickly coating every surface with moss and mulch and dripping ferns. Not ideal for examining field relationships…!

Fortunately, the rivers sample the host granite, and with the help of brilliant local geologist Rachael Baxter (University of Otago) I could get useful geological context for the orbs by studying the bedload. The orbs are exceedingly rare, and we found only one tiny pebble containing part of an orb – perhaps my most treasured pebble yet in a lifetime of picking up pebbles.

The people of Karamea are justifiably proud of the local “ringstones”. While asking around for permission to access land, we found plenty of folk keen to share their local history and show us their family rock collections. The Karamea Centennial Museum archives newspaper cuttings, photos (including an old Sedgwick Club photo!) and other documents relating to orb discoveries over the past hundred years, all invaluable for my research.

Our department slab comes from a boulder found by a local man, Levis Johnson, while deerstalking in 1943. Too large to be moved by one man, the boulder lay undisturbed until the construction of a logging road meant that a bulldozer, wire ropes and manpower could be borrowed to relocate the rock to Johnson’s lawn. The boulder was so remarkable that it made the local news. Upon hearing of the discovery, a government geologist named Pat Marshall visited Karamea to acquire it. Initially, he offered Johnson £5, which Johnson declined saying “if it’s worth that much it must be worth more!” After a telephone call to Wellington, Marshall got permission to pay £50 – Johnson reportedly felt like a millionaire! When a government truck arrived to collect the prized rock, the driver is said to have asked, “Where’s the boulder for Dr. Marshall that’s to be wrapped in cotton wool?”

I could certainly relate to Marshall’s concern as I meticulously padded my own samples for transport. This came back to bite me, when a customs official found my dozens of tiny baggies of tissue suspicious and made me unwrap every single chip of rock for inspection. After a clean swab test and a lot of granite, he shifted from suspicion to bafflement, then to amusement. By the end we were chatting about volcanoes!

Marshall thought the boulder so fine that it deserved to be displayed in as many museums as possible, so the government sliced up the rock and distributed specimens worldwide. I tracked down a number of the slabs during my research. Our slab’s closest cousin is on display in the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Visiting it was a surreal experience after studying our department’s slab so closely: like looking at your reflection through two mirrors.

Years on from my first encounter with orbs, I feel as though my analyses have resolved some mysteries but unearthed many more. We hope to have papers out soon. I like to think that everyone involved in our slab’s colourful history would be happy to know that it is still yielding exciting new scientific insights.

References:

Grapes, R., 1996. Saga of a unique boulder – Orbicular granite from Karamea, Geological Society of New Zealand Newsletter, 110, pp.19–22

Marshall, P., 1946. Spheroidal granites, The Australian Museum Magazine, Vol. IX no.3, pp. 74–78

Gordon, C., 2024. Insights into magmatic processes from the crystal orientation mapping of igneous microstructures. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge.