In part 2 of our series on the Sedgwick Museum and its role in reflecting new perspectives, Rob Theodore, Exhibitions and Displays Coordinator, discusses the greater role of representation in the Museum.

Using hashtags and subverting expectations

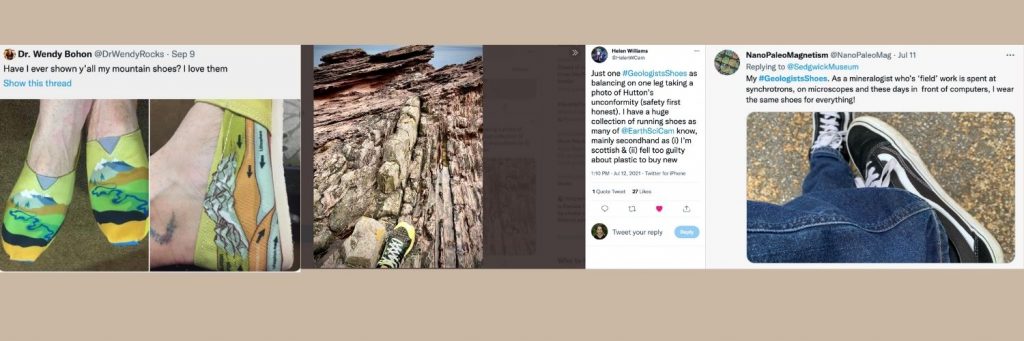

What is behind the #GeologistsShoes activity on Twitter and in the Museum?

Adam Sedgwick’s boots were an unusual acquisition for us – it’s not something we ever thought about having and displaying. But they are a key part of our Adam Sedgwick display. Everyone has a pair of shoes, I think you can get a lot more connection with shoes than a rock or fossil. When we heard that the boots were going on loan to Norwich Cathedral as part of ‘Dippy on Tour’ one of our colleagues, Matt, suggested, tongue in cheek, ‘why not put a pair of red stilettoes in there?”

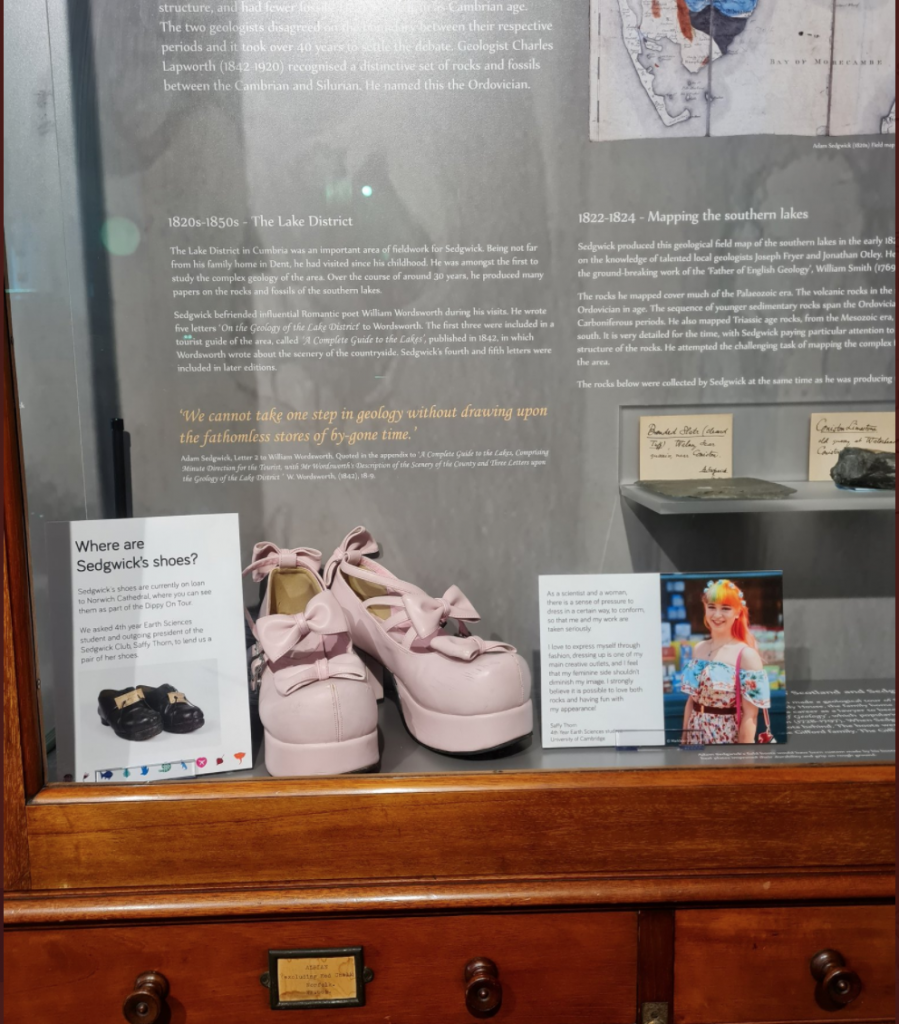

Adam Sedgwick’s shoes, packed ready to go to Norwich Cathedral for ‘Dippy on Tour’.

Saffy Thorn’s pink high heels on display in place of Sedgwick’s shoes.

Here in the Museum, we’re trying to talk about the issues around representation and subvert expectations of what geologists look like. We saw an opportunity to do this with Sedgwick’s shoes – our displays can be a bit traditional but we are trying to take opportunities to be more light hearted. I contacted one of our fourth year undergraduates, Saffy Thorn (who’s also a fashion blogger) saying ‘you’re a geologist, why not include your shoes?’ Her look is distinctive and quirky, so this was a chance to shift people’s ideas in a simple way. Within a week, her pink high heels were on display.

What has the reaction been so far?

We had a good response on social media to #GeologistShoes. Someone even shared an image of their moulded supports with their shoes, which help make fieldwork accessible for them. It was great that people felt comfortable to share that.

In person, some people have pulled a face or walked away from it and some people have really liked it. But if it doesn’t cause a strong reaction, it sometimes isn’t worth presenting something new, so those negative responses can be a good thing. Those people might go away and think about it and find their first reaction isn’t their lasting reaction.

It’s also enabled us to engage in more conversations around how people access Earth Sciences. Questions like, ‘What does your hammer mean?’, ‘Do you go out in the field?’ ‘Do you dig up dinosaurs?’, ’Do geochemists think about dinosaurs?’ There’s so much to unpick around what people can do in Earth Sciences. If I ask a student what they like studying and they say maths, I can tell them how maths is used in geology. If they say art, I can tell them the industry needs palaeoartists.

What challenges are you working through to bring better representation to the collections and the public?

We’re working much more closely with people in the Department through things like the research displays. Having a balance between the research and the researcher. We have them come into the gallery to talk about their research and to do events and speak to the public about their research. There’s been a shift from an exhibition for public engagement to being a bit more of a rounded offer where the exhibition has been one piece, and not even the most important piece, of engaging people with the science and the research/researchers.

We’re undergoing a cultural shift from things being on panels on the walls and with the objects trying to ‘talk for themselves’ to us being there and talking as people. We show a bit of what a researcher is like, how they look, how they dress – and it might not be what people have come to expect. The researcher’s personality can come through – they can crack a joke, they might be wearing a geeky tee shirt, they might be talking about what they don’t like of what they do. It helps us represent Earth Scientists better and from that we can get into the more challenging representations around race and gender and sexuality and neurodiversity. Seeing someone and talking to them is one of the best ways to do that.

Seeing people who look like you can be really helpful. For example, the current school curriculum mentions Mary Anning. Kids learn about female Earth Scientists and they read about different people in books. If they then come into the Museum, the ‘shrine to Earth Sciences’ where the actual people should be, but don’t see anyone who looks like the people they learned about, or like them, then it is a big barrier. We can be a key piece in changing that representation.

There’s a lot more that Earth Sciences can do to include more diversity and the Museum is a part of that work. Visibility is an important part of it.

Making Earth Sciences engaging and helping it to be something people can connect with without forcing it down their throat is a huge challenge. It has to be handled sensitively and that’s what we are trying to do.

Part of Duria Antiquior, on display at the Sedgwick Museum. The original was painted by geologist Henry De la Beche and prints of which were sold to support Mary Anning.

Mary Anning. Oil painting by an unknown artist, before 1842. Held at the Natural History Museum, London.

Does it become uncomfortable to be in a position to challenge things like this? For example, Mary Anning’s work being claimed by white male scientists or the fact some artefacts may be attached to slavery or colonialism?

What is uncomfortable for some might not be for others. It might be difficult to learn a new truth about an object or person, but we’re here to uncover information and that can be empowering.

People are interested in why Mary Anning’s name isn’t on the fossils or the paperwork and how she was treated. The story has gotten into popular culture – it’s in the curriculum and there’s a big movie out now. So people don’t feel it’s being forced on them. It’s more difficult to have the conversations about race and we are going to face challenges around the decolonising and the legacies of our collections.

It’s all quite delicate. As examples, Henry De la Beche, a geologist who supported Mary Anning, owned slave plantations. Money from those plantations would have gone to keeping Mary Anning afloat. Adam Sedgwick was a trustee for a plantation owner who owned slaves and Sedgwick benefited from the owners will. So materials in the museum are most likely to have been bought with that money.

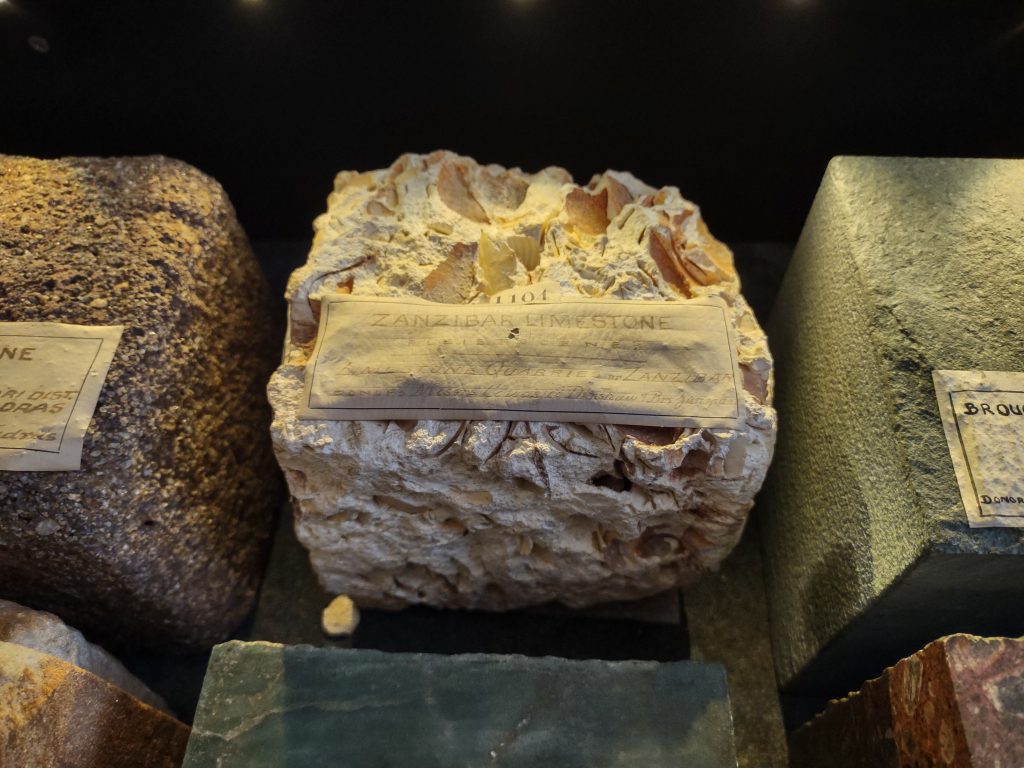

My family is from the Seychelles and the Museum has a piece of rock from Zanzibar, which was a port for the East African slave trade. There’s a very good chance someone in my family was locked up in a building made of that building stone. That building stone, the collection of building stones like that, are an incredible resource that lets us look at colonial situations another way.

With our historical collections, everything can be woven through with something troubling and it’s good to for the Museum to acknowledge that. Uncovering new information, talking about what it was like when objects were collected, talking about the history around the time collections were made and viewing them from that perspective is a chance for us to say ‘this is where we come from. We can’t change that, but we can work from it.’

On your next visit to the Sedgwick, see if you view the collections a little differently. You can speak to any member of the team on site, if you’d like to know more about any displays or objects or would like to know more about your own collection.

Keep up to date with the Sedgwick Museum on social media, by following them on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.