Cambridge Earth Sciences PhD student Zhenna Azimrayat Andrews visited the Ocean Rainforest Inc.’s (ORI) pilot kelp farm, off the California coast, last summer. The results Zhenna gathered alongside an international team will help her construct model simulations of carbon capture using kelp farms. Zhenna reports on her fieldwork here.

Marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) strategies, such as the use of kelp forests, are gaining traction as promising technologies to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Researchers from Cambridge have united with Stanford University, along with other universities in California (UC Santa Barbara, UC San Diego, UC Irvine), for an international collaboration researching mCDR.

The Santa Barbara Channel is home to Ocean Rainforest Inc.’s (ORI) pilot Californian kelp farm (growing Macrocystis pyrifera). Through ORI’s partnership with Stanford and their collaborators, the site is being used to collect data on the fluid dynamics, biogeochemistry, and carbon dioxide removal potential of kelp farms. Gaining information for all of these factors will help to better understand kelp forest growth, and how it can be utilised as an mCDR technology.

I am a PhD student studying in the Department of Earth Sciences and I visited Santa Barbara in July this summer to help with this data collection. The environmental data collected from this international expedition will be used by me and the team back in Cambridge to improve the OceanBioME modelling environment, with Cambridge Earth Science’s Prof. Sasha Turchyn, and Prof. John Taylor and Jago Strong-Wright from the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics (DAMTP).

The expedition was carried out over four days and consisted of a variety of observational and data collection methods.

On day one, Monday the 15th of July, Prof. Kristen Davis (Stanford) and Prof. Geno Pawlak (UC San Diego) conducted observational scuba dives along ORI’s farm lines, to monitor growth rates of the giant kelp. These observations were used to plan the week’s data collection efficiently and carry out assessments on the progress of the kelp farm’s growth.

Day two comprised instrument and data recovery. The researchers used a machine named the “wire walker” for collecting a myriad of different data points. It is a scaffold which houses sensors monitoring the light availability, pH, carbon content of the water, and more. Throughout a period of collection, it “walks” its way up a suspension cable, collecting these data from different depths over a period of time. During its time in the water, it develops what the researchers call its furry coat (of algae), and it must be taken apart to be thoroughly cleaned in between each round of data collection. Once this is complete, its data can be downloaded, and it can be prepared to be redeployed. This meant that I had an afternoon at UCSB’s oceanography lab to become very acquainted with the wire walker, UCSB’s resident pressure washer, and lots of tag-along shrimp unfortunately making their home in the wire walker’s furry coat.

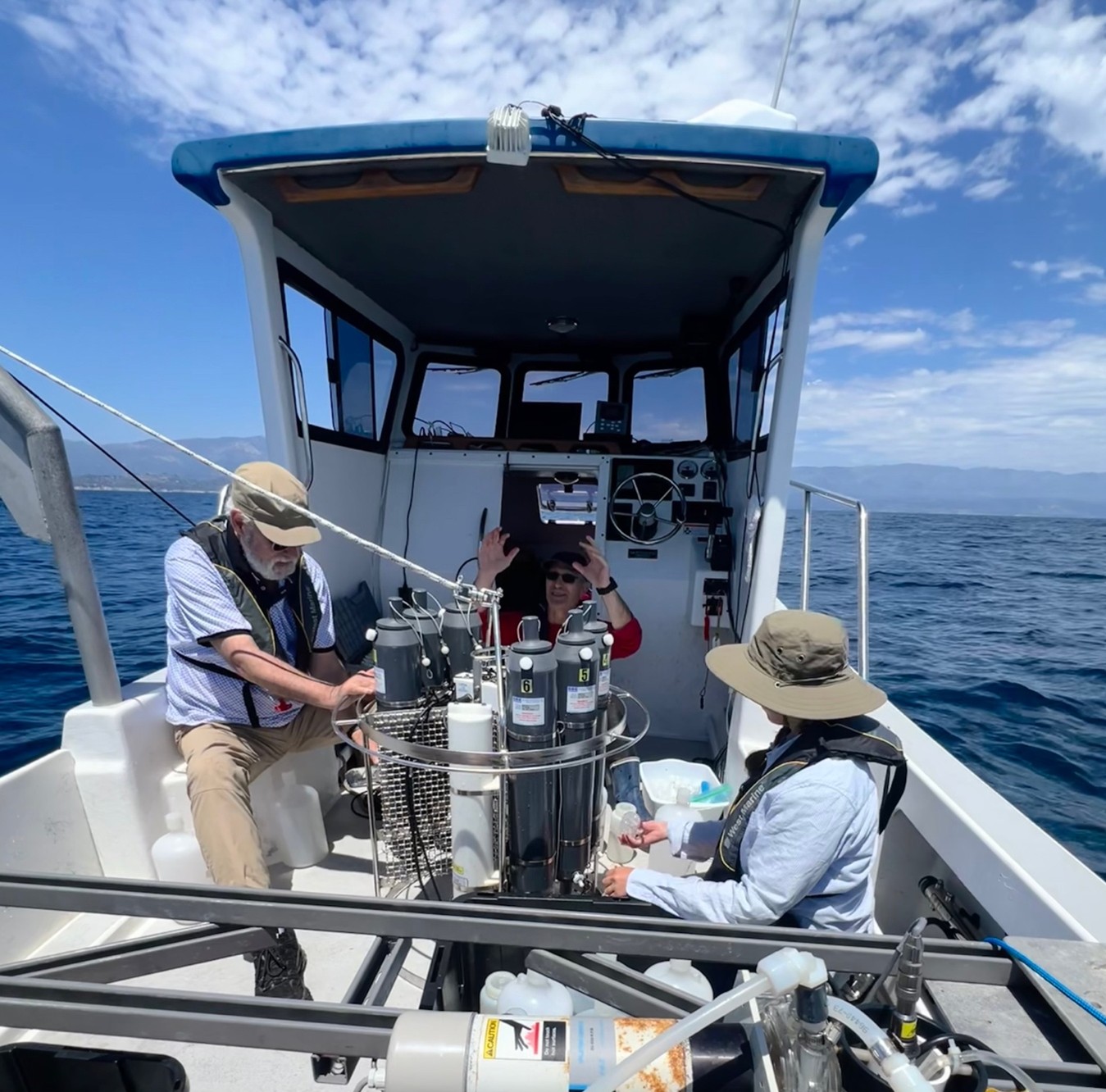

Days three and four of the expedition were biogeochemistry days and the team visited the kelp farm and took samples from the water both upstream and downstream of the farm. These were taken using CTD casts which are testing for pCO2, O2, and pH at different depths. The results of these casts should indicate how much carbon dioxide is absorbed by the kelp as water flows through the farm, and this data will be used in Cambridge to improve the accuracy of our kelp forest models.

This expedition allowed me to understand where my data is sourced from and the effort, preparation, and teamwork which goes into obtaining it. The trip was successful, notwithstanding the reliable speed bumps which accompany fieldwork, and I am now looking forward to applying what I have learnt to my studies which begin this Michaelmas term.

Feature image credit: Jenny Adler.

This blog was originally published by Cambridge’s Centre for Climate Repair.