The last time I blogged about WACSWAIN was in January 2019, when we were in the euphoria of having drilled to the bedrock at Skytrain Ice Rise, and retrieved 651 metres of ice. So what have we been doing since then?

Well, firstly the ice had to travel safely (i.e., cold) to Cambridge. Our 130 boxes, each containing 4.8 metres of ice, were stowed in the -20°C freezer containers on the RRS Ernest Shackleton. The temperature loggers, which we left in some of the boxes, confirmed that the samples had safely survived the heat of the tropics when they arrived in the UK in early April.

Next came the hard part: the basic processing of the ice to produce sections for analysis. This word “processing” disguises a production line, with two teams of three people spending several hours each day in the cold room. Their task is to convert 80 cm long cylinders of ice into six separate cross-sectional strips devoted to different analyses. This process involves a bandsaw, numerous pre-cut plastic bag sleeves, and cold fingers. It was probably only possible because in parallel to the processing rota there was a cake rota, so we ended up cold but well-rounded! The process had its ups and downs: the ice at around 400–600 metres depth, which we knew was a little fragile in the field, turned out to have numerous internal cracks that made it very hard to coax broken strips of ice into bags. However, just as we were despairing, we found that the lowest 50 metres—the most precious ice, where we expect to find the ice from the last interglacial period—was in much better condition, with many sections unbroken and ideal for analysis. The whole extended team of WACSWAINers, and our Cambridge and BAS colleagues really worked hard on this unpleasant task.

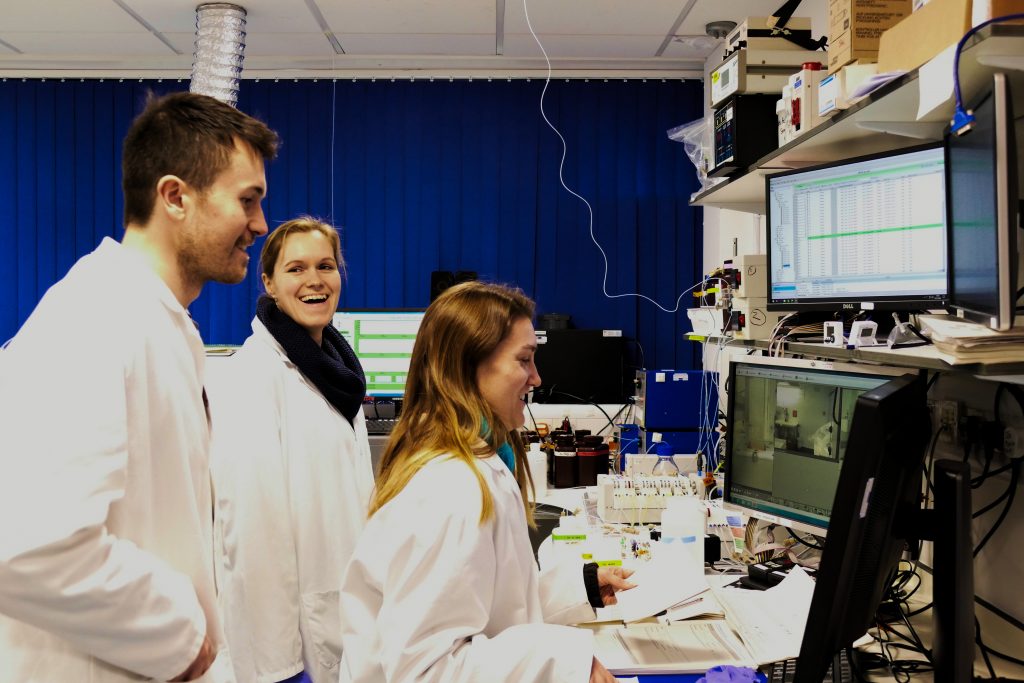

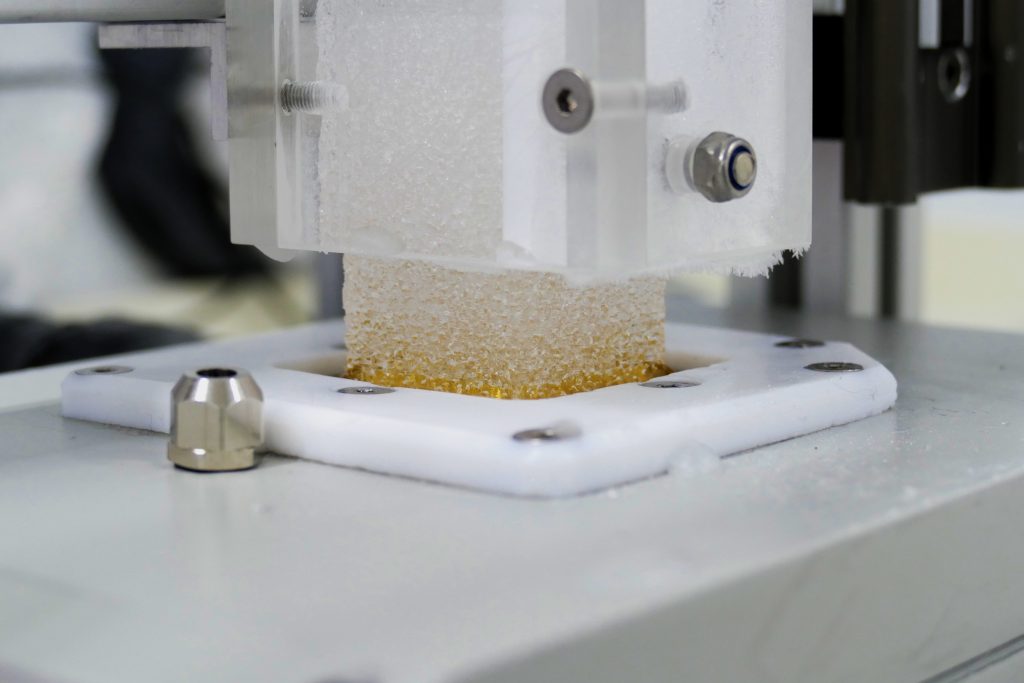

Of course our aim is to carry out chemical analysis of the ice. For many of the analyses, it has become commonplace to use a continuous flow analysis (CFA) system, which involves placing a section (about 3 x 3 cm cross-section by 80 cm long) on a warm melter plate in the cold room. As the section melts (typically 3 cm per minute), water is sucked into a number of instruments in the warm laboratory, and the air from the bubbles is directed to a methane analyser. The plan was to use around a dozen different instruments to measure: water isotope ratios; metals; major ions, like sulfate; dust particle number; methane; and other analytes. Again this process sounds simple, but involves a complex system where: all the instruments have to be operating well at the same time (unusual in any lab); water has to reach them at the right flow rate; and automated sequences have to supply them with blanks and standards, and log the data.

Three people have spent several weeks making this plan happen. Mackenzie, who many of you will remember from previous blog posts, is our ice core postdoc and was in the field at Skytrain Ice Rise. Helene, who joined us as a postdoc over the summer with the main task of setting up another analytical system, is working on the CFA for now. She has even more Antarctic experience than the rest of the team, having recently spent a year running the air chemistry lab at the German Neumayer Station. Jack, our newest recruit in the team at BAS, will be responsible in the long-term for their analytical programme.

In January this year the system was ready to go. The team are now melting ice and accumulating data on all the instruments. To be honest, we haven’t had time to see what the data say, but just seeing the screens full of wiggly lines is exciting. At the time of writing, the team are at 60 metres depth (probably sometime in the 18th century), and managed 15 metres on their best day. So there are many weeks of production line analysis to come. But at least we have started, and by the summer we should have a huge volume of data, which will provide a first idea of what happened to the ice shelf and ice sheet around Skytrain Ice Rise in the last 150,000 years.

Fascinating to see all the boxes of extracted ice stacked up, waiting to go on the long journey back to Madingley! Do the analytical processes use up all of the ice cores? Or is a section kept aside as a spare, or backup?

Thanks for your question. We try to keep an archive for all cores. Each 80 cm length has been cut into sections. Half the core section is labelled as “archive”. We will be using some of that for trace gas measurements later, but we will be aiming to keep at least some of the cross section for every length for many years.

I should add for context that I am also responsible, as chair of the science committee, for the remaining core from the European EPICA Dome C ice core (the 800,000 year core) that was drilled nearly 20 years ago. We actually cut that one in the field and left a quarter of each core in a sub-ice container to limit the risk from transporting the other 75%. There is still something left in the core store near Grenoble of every core from that although in some cases what is left is only about 15% of the cross section.