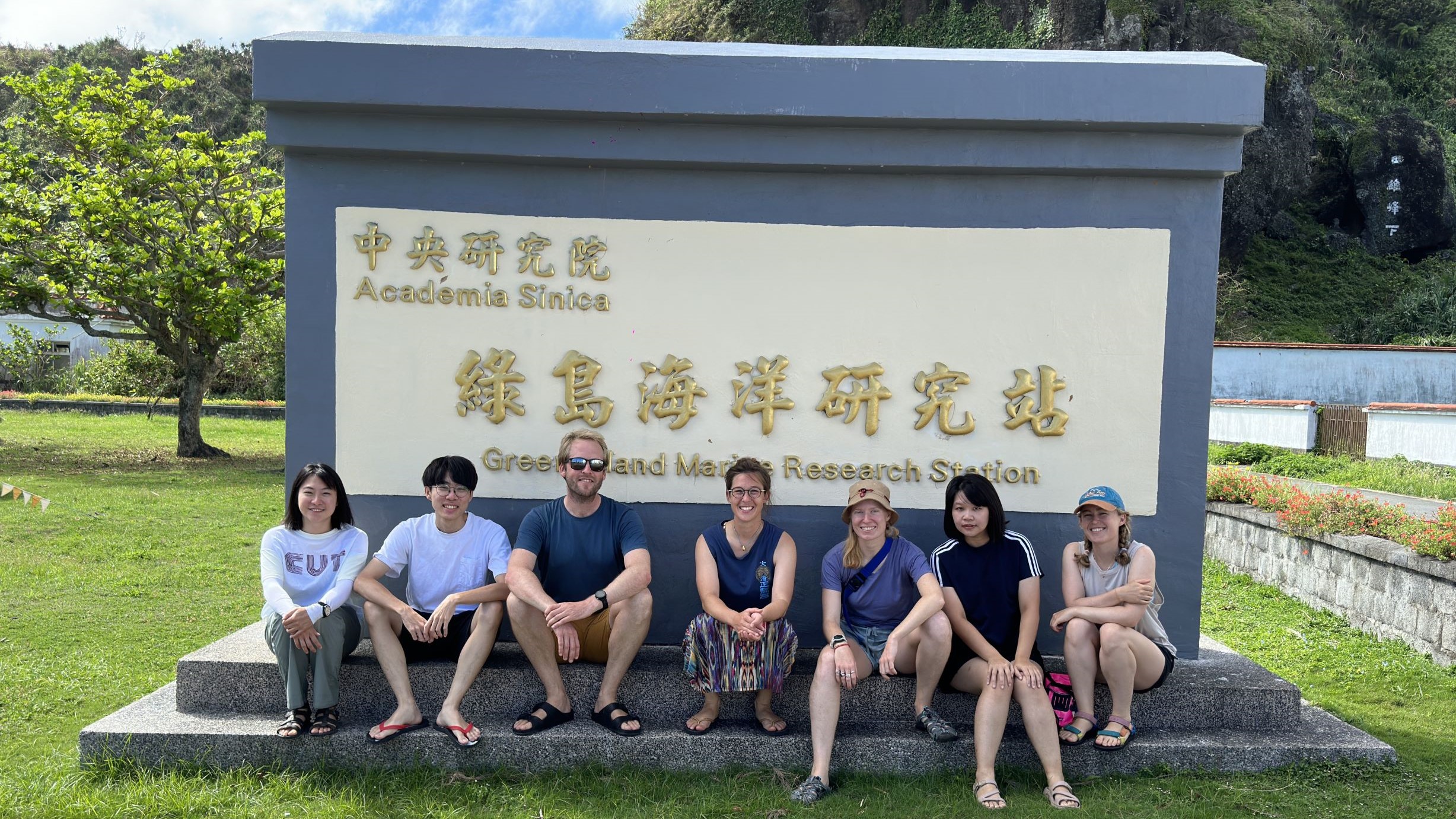

This summer a team led by Dr Oscar Branson, including myself and fellow PhD students Winnie Fang and Alice Ball, headed to Taiwan for five weeks. We were on a mission to catch and culture open ocean plankton (specifically foraminifera) and our aim was to understand how they build their shells.

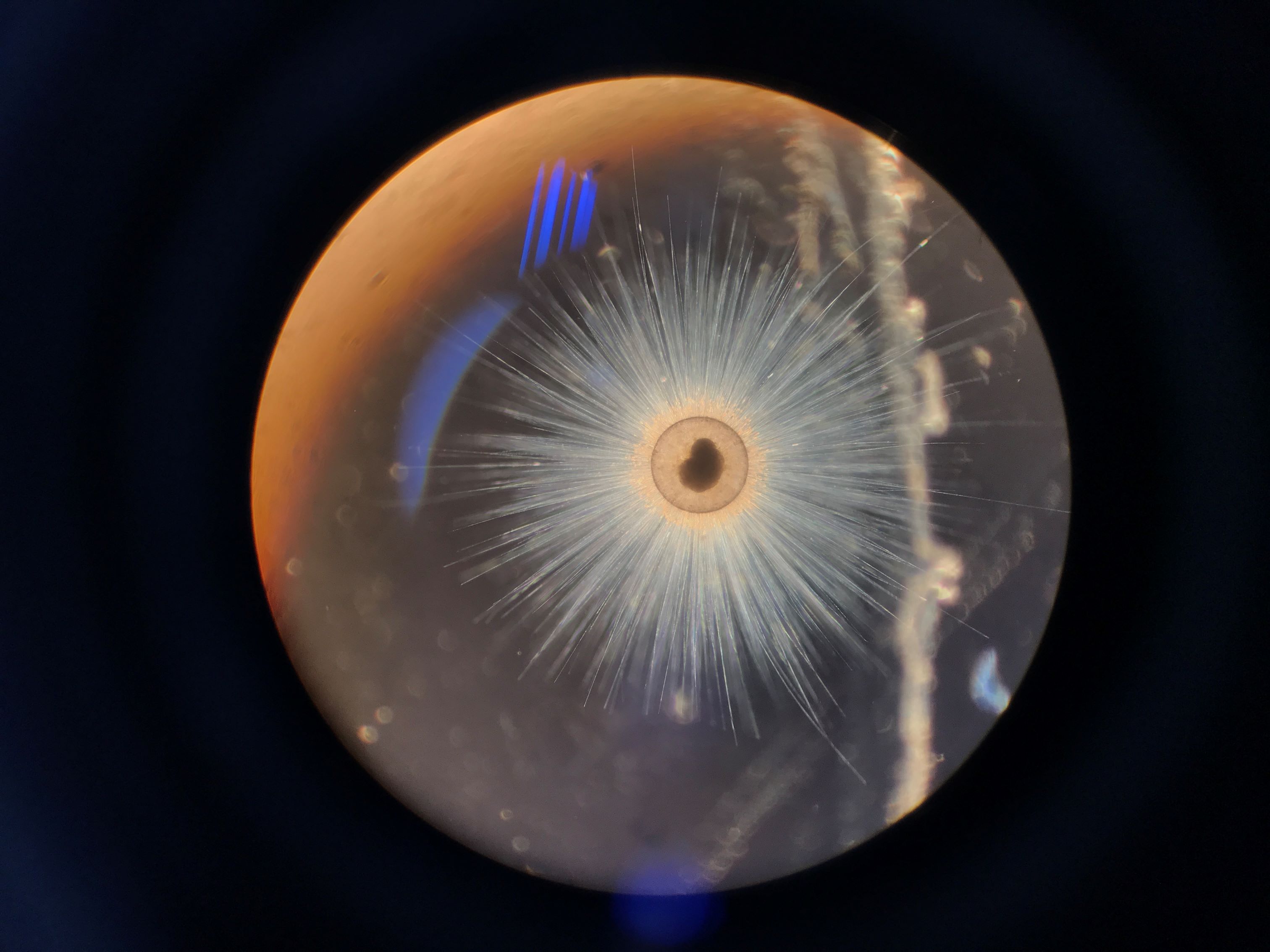

Although individually very small (up to only a few millimetres), these single-celled marine organisms have a large impact on the global carbon cycle. The calcium carbonate shells that these ‘forams’ build remove carbon from the seawater, and contribute to its burial when they sink to the seafloor and become part of the sediment. As well as trapping carbon, these shells hold a snapshot of the environment in which they formed, making them an important archive or ‘proxy’ of past ocean conditions and climate.

A trip to Green Island

There aren’t many places in the world where you can work with planktic forams. You need a rare combination of easy access to open-ocean water, close to a well-equipped marine lab. Green Island, a small volcanic island off the eastern coast of Taiwan, has both!

The island sits right in the flow of the Kuroshio current, which brings surface ocean water in from the Pacific and up the east coast of Taiwan, to China and eventually Japan. It’s the Pacific equivalent of the Gulf Stream. This means the water you find after a 5 minute boat ride from Gongguan harbour is very similar to the water you find out in the open Pacific Ocean. The easy access to these open ocean conditions is unique, and makes Green Island a perfect place to work on foraminifera.

But how do we get these forams into the lab to study? For the best chance of returning with happy, healthy forams, we catch them one at a time by hand while SCUBA diving. Given their teeny size, the disorientating nature of blue water diving, and fluid physics, this is a skill that can take some time to master. With a range of expertise and experience amongst the dive crew, we dedicated our first week to brushing up on SCUBA diving skills, completing additional training, and practising the collection protocol.

Island life: Not all sunshine and rainbows

We arrived in late August between the typhoon season and the winter monsoon. The first thing to hit us was the heat and humidity. With the sun shining it wasn’t long before we settled into the relaxed pace of life. A popular island for diving enthusiasts and tourists alike, scooters are the preferred form of transport. There was no shortage of cafes, exotic fruits, spectacular views and welcoming locals happy to share the culture and history of the Island; a story involving prisons and political activism.

The research centre (where our accommodation and lab were located) was in fact part of the Green Island White Terror Memorial Park, which commemorates the victims of the White Terror, a time of political oppression in Taiwan. This was due to the building’s use as a training centre for the Green Island prison until the late 1980’s. Just across from our building sat the crumbling remains of the old prison.

The calm sunny days of our first week were ideal for completing the busy schedule of training and practice dives we had lined up. It also gave us a chance to explore the island’s coastline, from busy fringing reefs, deep water soft coral beds, bustling anemone cities and mysterious harbour ecosystems in the dark. We encountered turtles, sea snakes and schools of barracuda, arm length sea cucumbers and flamboyant nudibranchs, and a wealth of hard corals. It had us all madly gesturing and gurgling with excitement underwater.

It therefore took us by surprise to learn that during week 2 we would be graced with a typhoon. With the fridge stocked, the storm shutters secured and our dive boat relegated to the shelter of the harbour, we braced ourselves for the arrival of Typhoon Soala. Although mild winds brought rain to the island, a last minute path change meant that we avoided most of the brunt of Soala.

The relief was short-lived however, because after only one day of freedom and our first successful foram collection, we got news of typhoon number two. Haikui was on a direct path for Green Island. When it made landfall it brought with it howling winds of up to 150 km/h that rattled the windows and hurled vertical sheets of rain against the building. Several windows were smashed in and sections of the roof peeled away, but we were the lucky ones – some buildings on the Island were reduced to rubble. Despite small landslides peppering the mountain roads, and losses to power and water, everyone on the Island was safe.

Once the skies cleared and the seas calmed, foram collecting was a go; now with new urgency having lost precious time . We fell into a routine of early morning diving, back to the Research Centre for breakfast and ID-ing our catch, followed by afternoons spent preparing new cultures, feeding hungry forams, and observing their growth.

So what exactly were we doing with the forams in the lab? Alice and Winnie share their research motivations and detail the experimental protocols that kept them busy in the lab. From foram physiology to environmental proxy development, there were a number of questions we hoped to answer whilst on Green Island.

Research Focus: Respirometry

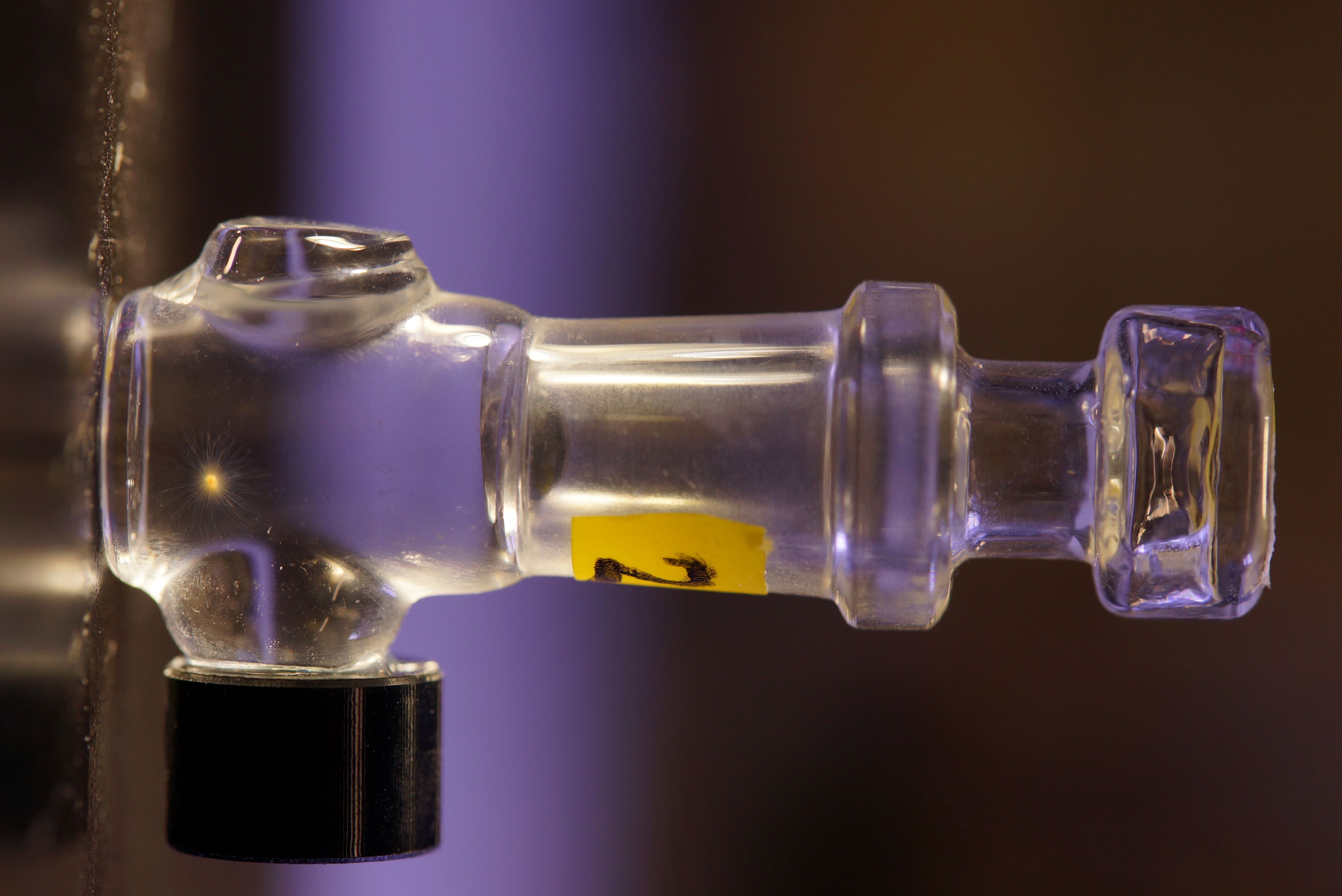

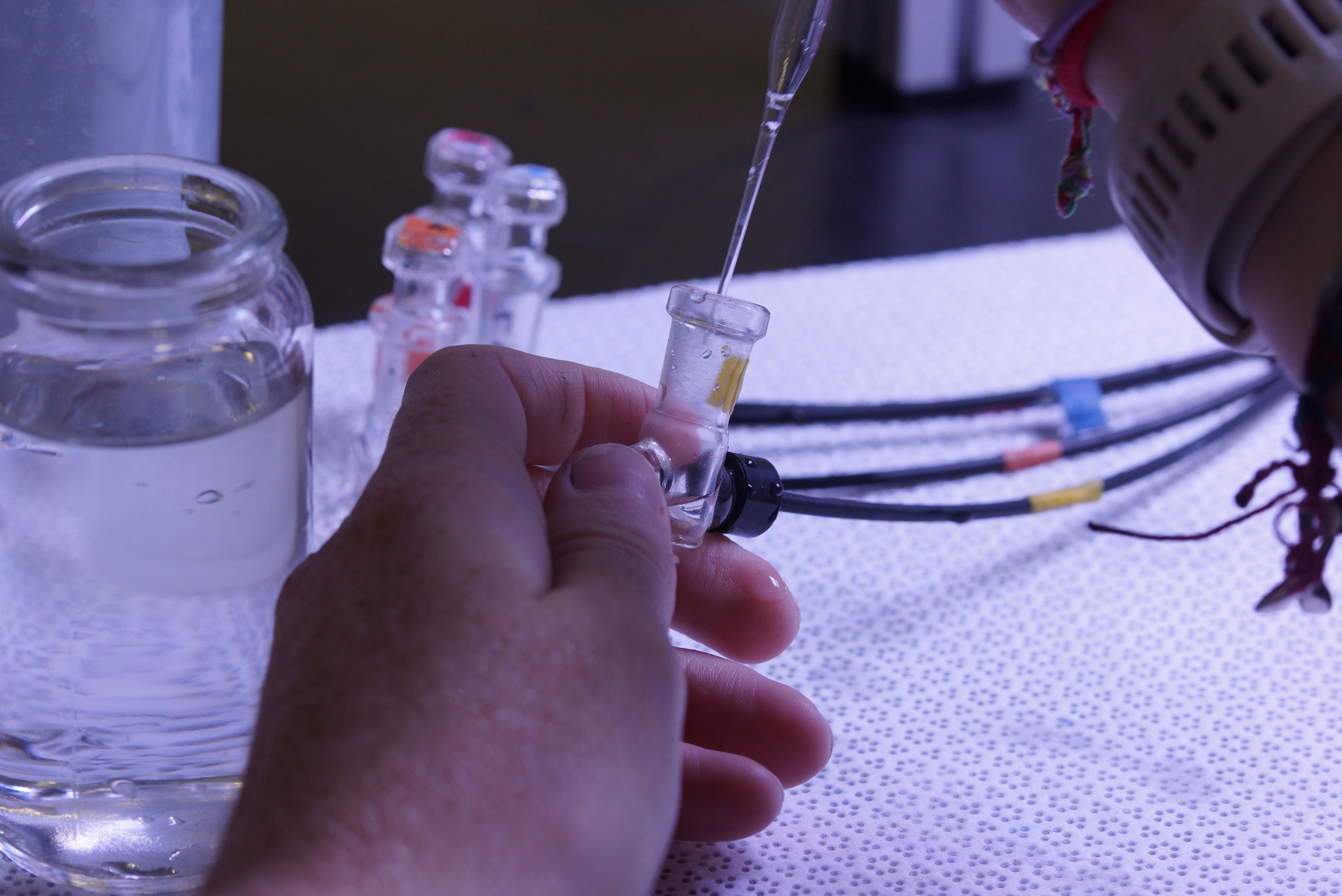

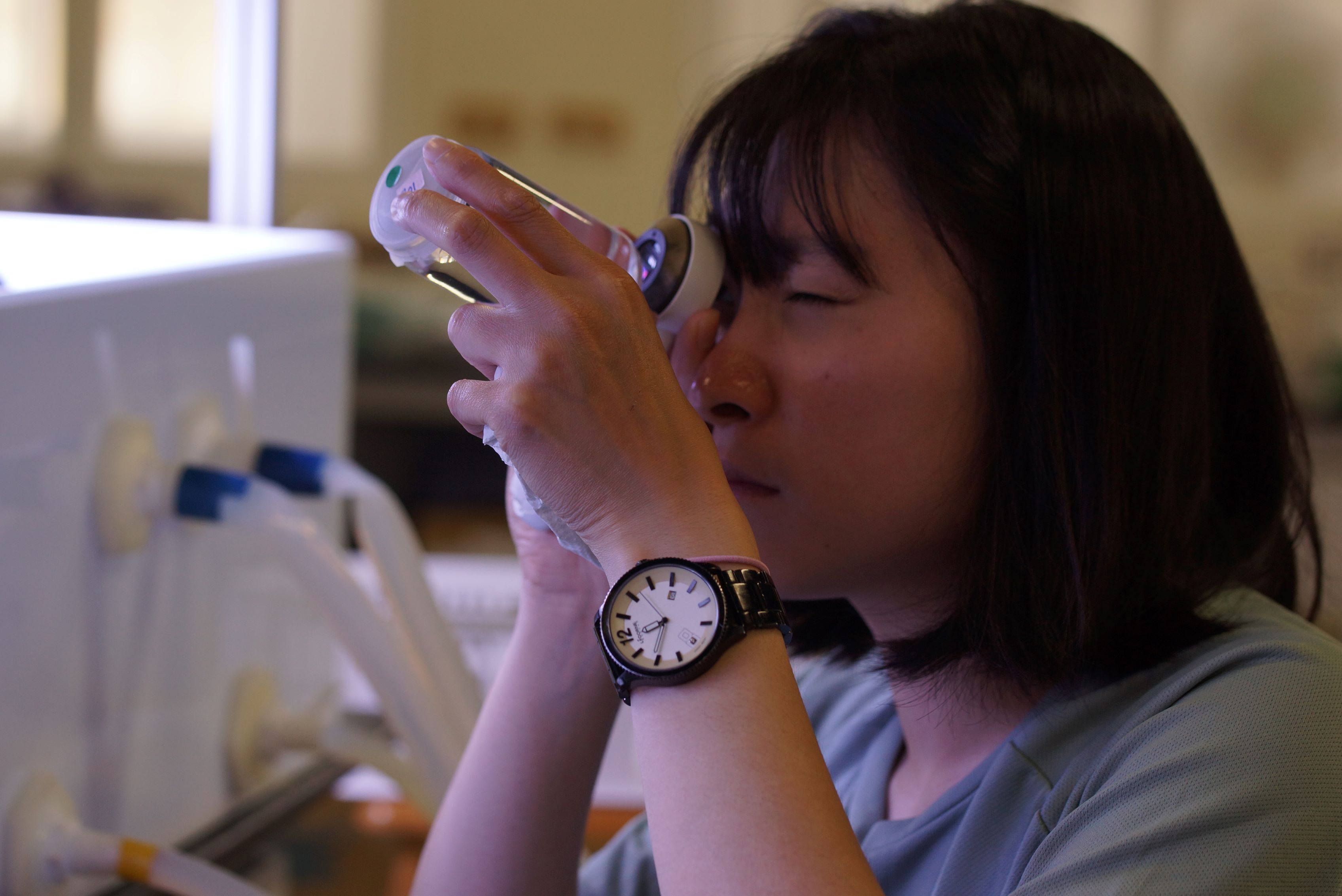

One of our aims whilst in Taiwan was to develop a new way to measure planktic foram respirometry. For context, respirometry refers to the measurement of the photosynthesis and respiration of a marine organism. To measure it, we put individuals of the same species in separate transparent chambers (pictured below), while sensors attached to the side of the chamber measured temperature and oxygen levels inside.

We also ran trials in light and dark conditions to see how this impacted respiration and photosynthesis. By hooking the sensors up to a computer display, we could monitor real-time metabolic rates and from that calculate photosynthesis, gross photosynthesis, and dark respiration rates. This information can be very useful for understanding an organism’s response to various ocean conditions, because changes in respiration and photosynthesis rates can sometimes indicate a physiological stress response.

We had a few RESP-fests (as Alice named them!)… basically an all-day ‘fest’ where we measured foram oxygen rates from 6 am to 6pm. We measured the same forams throughout the day in order to see if their respiration/photosynthesis rates might follow some type of circadian rhythm. We were also interested in whether a higher concentration of pCO2 in the water could influence foram respiration and photosynthesis rates.

Research Focus: Climate and Proxies

Forams are a key tool for palaeoclimate reconstructions. We can learn a lot about how they record proxy climate information through culture experiments. In the lab we can control the environment and test how sensitive a specific proxy (such as the trace element contents of a foram shell) is to a changing environmental factor. Our ongoing research is to look at strontium/lithium (Sr/Li) in a foram shell as an indicator of the carbon chemistry of seawater.

One of the big unknowns we hope to tackle is what this proxy actually stands for. Does the shell Sr/Li reflect changing pH, alkalinity, or total dissolved carbon? Or does it perhaps fluctuate with background Sr/Li variations in seawater? To investigate all the potential controls mentioned above, we changed each environmental factor one at a time, whilst making sure our forams were happily growing. The shells were collected, and the Sr/Li of the chambers will be measured soon in Cambridge!

After an intense five weeks, with more than a few twists and turns, we set about dismantling the lab with a sense of triumph. Despite two typhoons, delayed shipments, broken boats and uncooperative pCO2 levels in the lab, we had hit all of our experimental goals. We left armed with new and exciting insights into the circadian rhythms of planktic forams, and with a suite of samples, holding geochemical insights ready to be unlocked.

If you are interested in more details about the trip or want to stay up to date with this research as it emerges, head to our Lab’s website.

This blog post was jointly written by Madi East, Winnie Fang and Alice Ball.