Walk into the Sedgwick Museum and you are instantly immersed in a realm of fossil beasties: from the iconic Iguanodon from which the Museum derives its logo to the recently-discovered giant millipede, Arthropleura.

The Museum is perhaps less well known for its rock and mineral collections, which are of international scientific value and also serve as a key resource for teaching and research in the Department of Earth Sciences and elsewhere.

In this blog post, Robert Seidel, Collections Assistant at the Sedgwick Museum, tells us about the significance of the Petrology Collection for geoscientists both past and present.

What is the Petrology Collection?

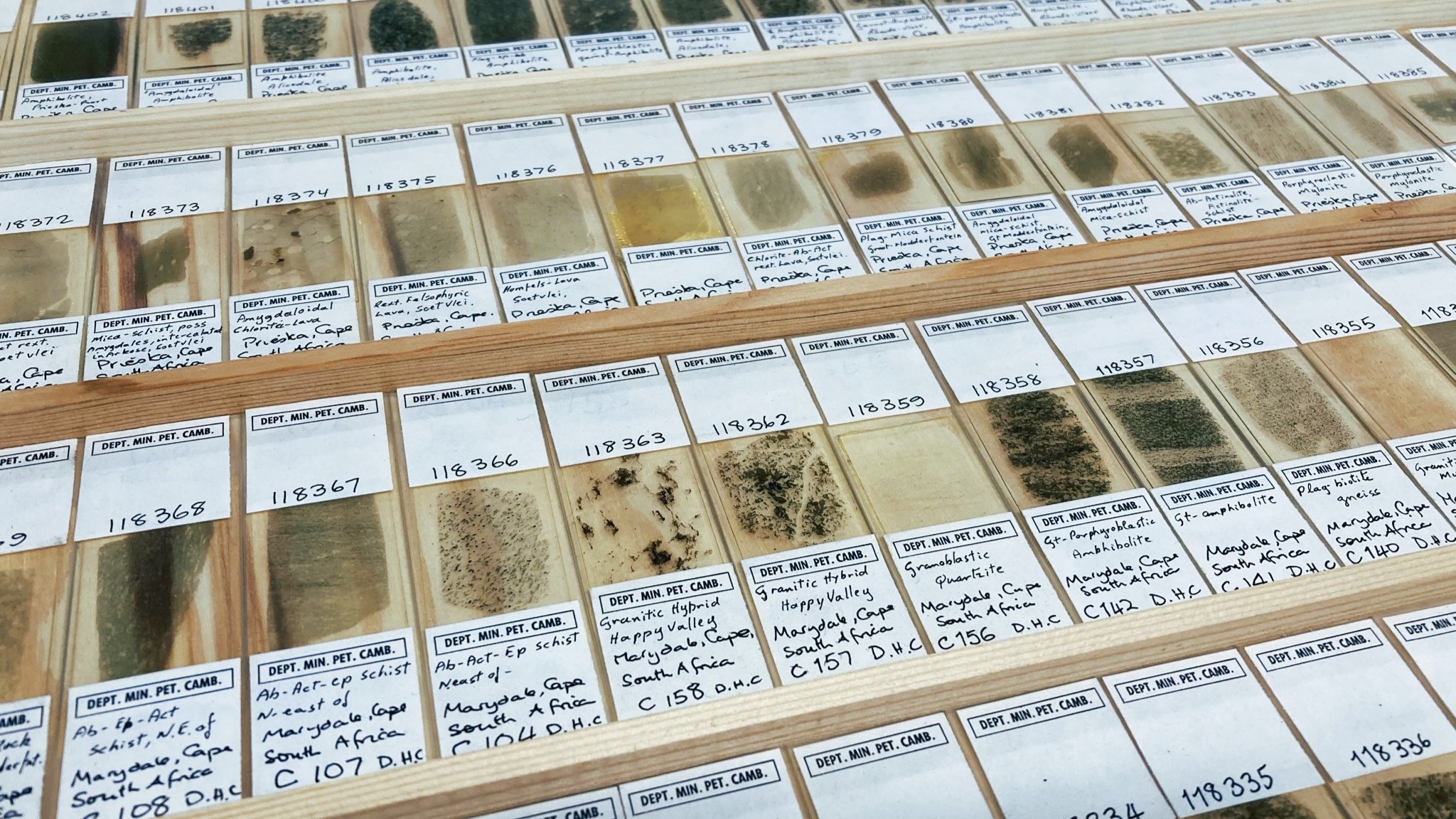

The rocks and minerals on display in the Sedgwick Museum are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of our collections. Behind the scenes, we have about 160,000 rock specimens and 250,000 thin sections, coming from around the world: from the top of Everest to the floors of the oceans.

The Petrology, or Harker Collection, is named after the eminent Cambridge petrologist Alfred Harker (1859-1939), who spent years amalgamating existing collections in the early 20th century. Over the last four years, the Collection has been moved into the Museum’s new purpose-built storage facility in West Cambridge.

What are your favourite specimens in the Collection?

What I find remarkable about the Collection is its global reach — through my work I get to see more variety than the typical geologist would see in a lifetime of work.

One of my favourite, more glitzy, minerals is a purple-blue metamorphic mineral called yoderite, which is only found at two locations in the world. The sample we have came from the type-locality in Tanzania, where it was first described by the renowned Cambridge mineralogist and crystallographer Duncan McKie in the 1950s.

A couple other spectacular mineral samples stand out from enquiries to the Museum. One, a perfectly cubic halite, was of interest to a researcher looking to investigate the Messinian salinity crisis, when the Mediterranean dried out during the Miocene. The Science Museum in London also enquired about a chalcopyrite sample from a Cornish mine for a potential exhibit about batteries.

What kind of stories and histories do the rocks reveal?

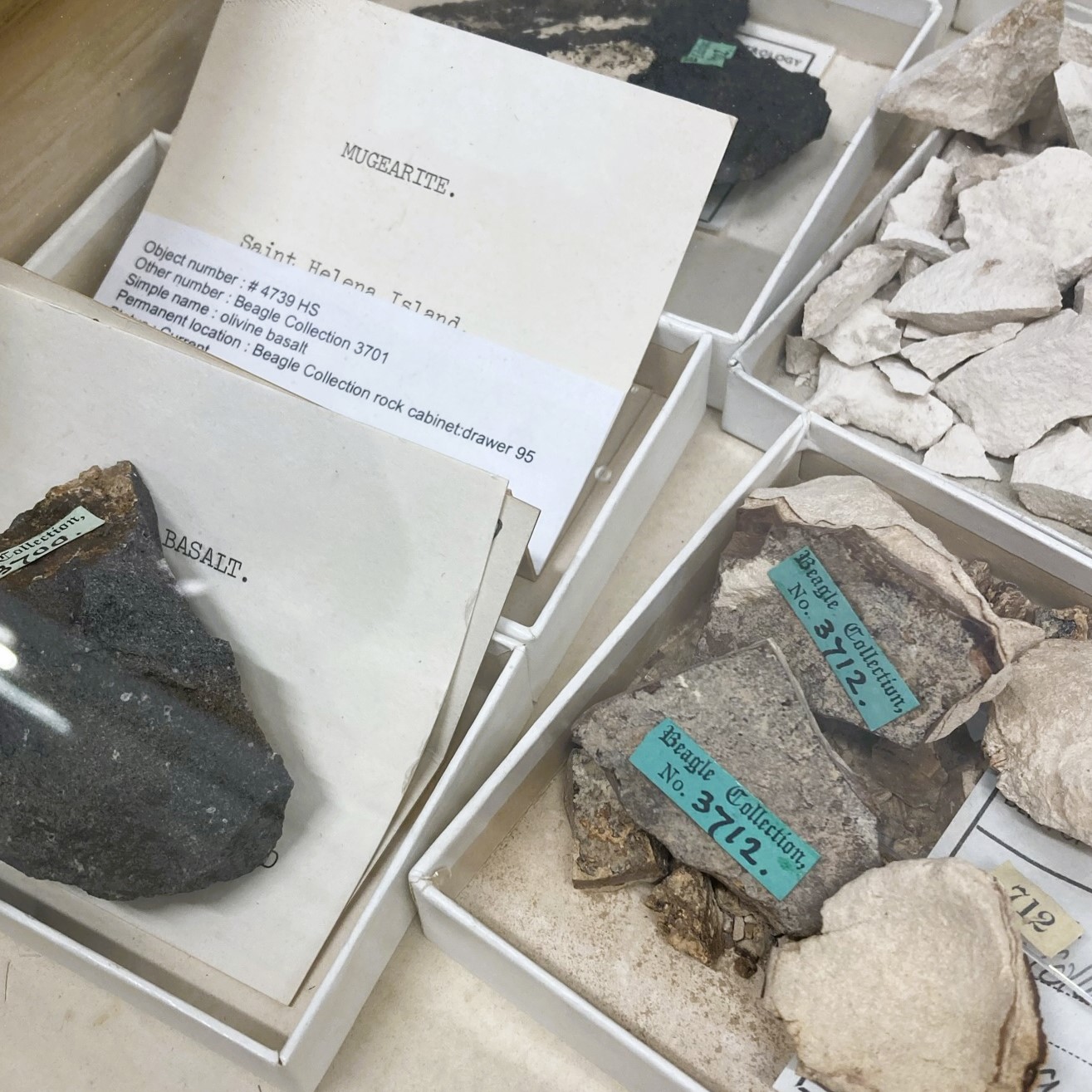

Visitors to the Sedgwick Museum may have seen our Darwin the Geologist exhibit, containing rocks Darwin collected on his voyage around the world on H.M.S. Beagle between 1831—1836.

Tucked away in our stores are thousands more Beagle samples, and the labels on these rocks often show how important they were to future generations of geologists. For instance, Alfred Harker revisited the Beagle samples and assigned new rock classification (including labelling the newly-coined rock type ‘mugearite’) according to his own research on igneous rocks from Scotland. That example highlights, I think, why these collections need to be preserved for posterity.

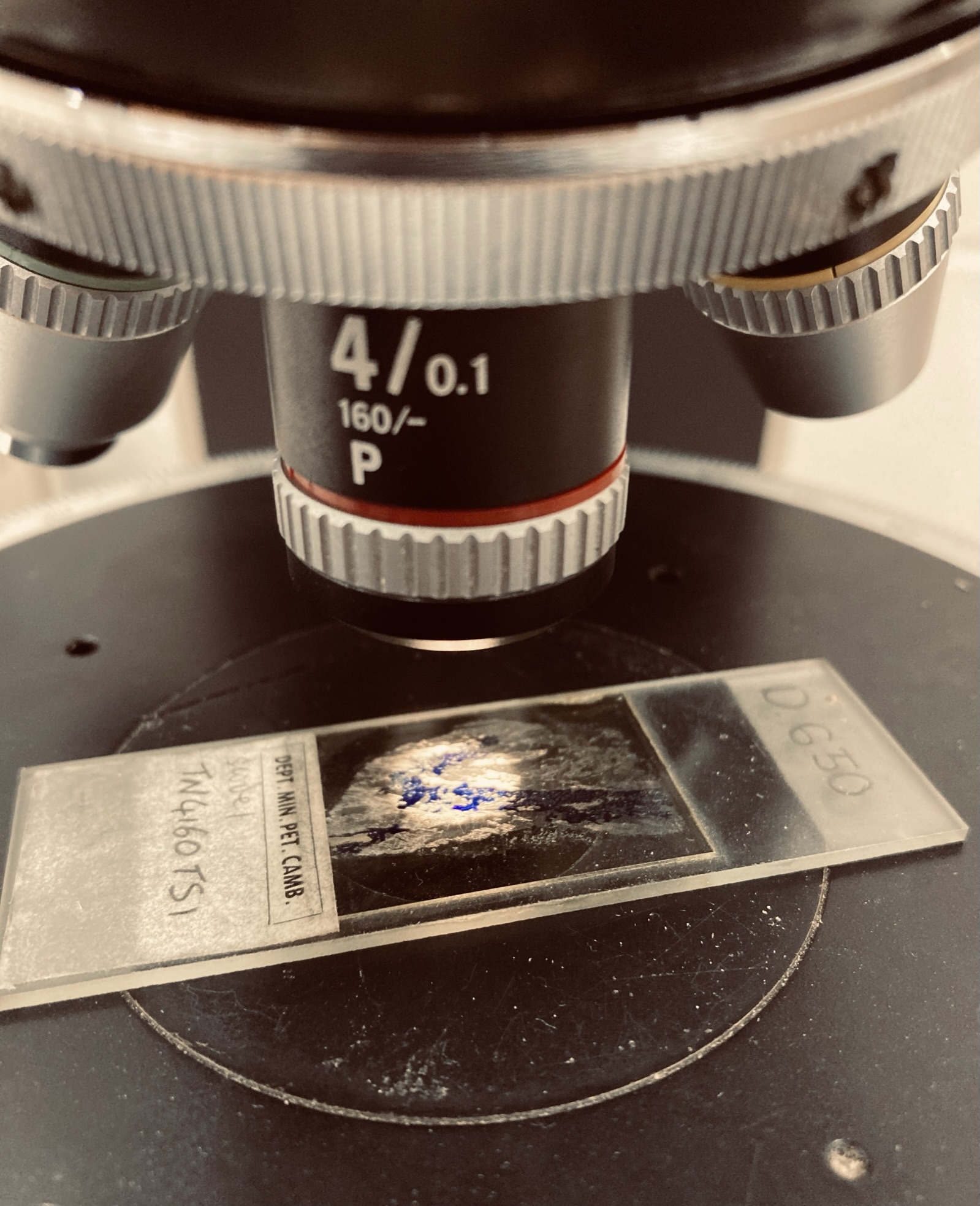

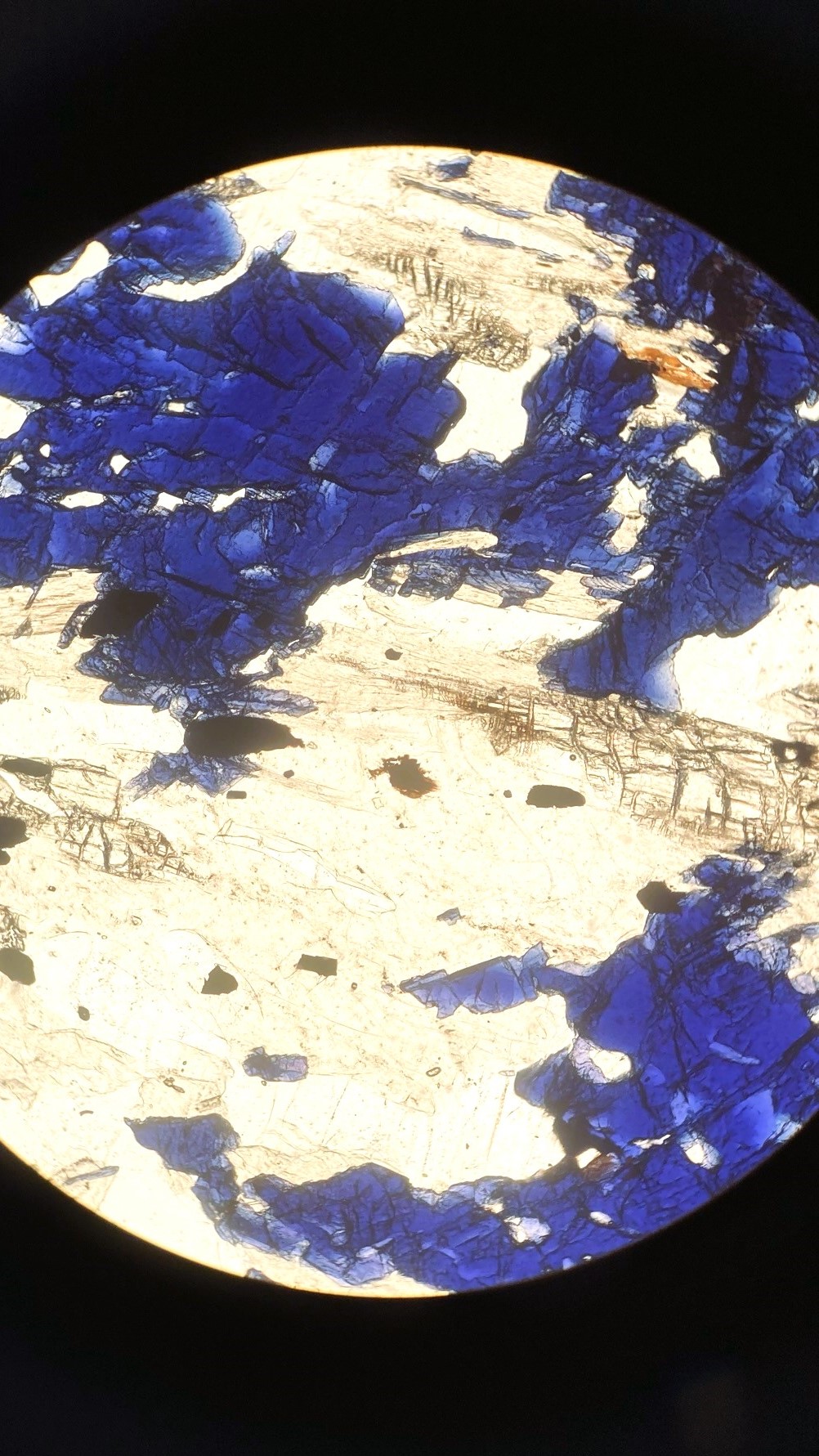

Famous geologists crop up frequently in the Petrology Collection. I’m currently archiving thin sections collected during PhD projects. As well as samples collected by Harker himself, who first introduced the use of the petrographic microscope, names like Michael Le Bas also show up. Le Bas pioneered work on the process of magma contamination.

Why might researchers be interested in these collections?

We think that about a quarter of the samples in the Collection are referred to in international scientific literature. Years after these classic rocks were first collected, researchers continue to work on them.

One example is our collection of metamorphic rocks from NE Scotland, the type area of Barrovian metamorphic zoning as first described by George Barrow in 1912. With samples collected by Barrow and researchers following in his footsteps, this is one of the largest collections of its kind anywhere in the world. That collection still gets a lot of attention from researchers who want to revisit those classic studies.

We also have samples, including drill cores, from different levels of the famous Skaergaard intrusion in Greenland. It’s a fossilised magma chamber that allowed us to understand processes like crystal fractionation and settling. Professor Marian Holness uses this collection for her work on layered magma intrusions.

I think there is something for every petrologist in our collection, including those with an interest in the social history and development of geology as a subject.

Hi, I just came across your collection via an Instagram post. Could you let me know if it’s possible to come and explore the collection and do some research? I’d love to find out the stories behind some of the samples and take photos if possible. I’m a painter, you can see examples on my Insta profile @paulamacarthur_ & website paula-macarthur.com

Hi Paula, great to hear you are interested in the Sedgwick Museum’s collections. The collections are open for queries, and my colleagues in the Museum would be very happy to help you out with details of the samples. You can find contact details on the Museum website here: https://sedgwickmuseum.cam.ac.uk/collections/collections-research-centre. Best wishes, Erin — Communications Co-ordinator.