It was an emotional journey. Nose pressed to the small oval of glass as London City Airport was left far below, I smiled wistfully down at the River Thames, golden in the rising sun’s first rays, as it made its final sweeping arc to meet the sea. The cut-out shapes of the Kent marshes, and the Isle of Sheppey beyond; home to a plethora of birdlife now as ever, is a place of special significance for me. Not only was it the intended destination of my first ever birdwatching trip, aged nine, but from this same London Clay Formation laid down in the Eocene, over 50 million years ago, came the first fossilised skull of a very remarkable bird. With jaws lined with bony projections of different sizes, like lobster claws, it was unlike any bird known.

The pelagornithidae, or pseudo-toothed birds—the subject of my PhD—were the world’s predominant seabirds for over 50 million years. Creatures of paradox and mystery, we still don’t know how they lived, where they fit onto the avian phylogenetic tree, or what brought their eventual extinction.

It was birds that led me on my journey into academia. While an interest in them might have brought most people straight to the sciences, for me the trajectory was thrown off course by an over-ambitious schoolteacher and an unusual talent for drawing. Instead of going on from school to study zoology or palaeontology, I was thrust, kicking and screaming, into a career in Fine Art. It turned out I was exceedingly good at it and I didn’t yearn for the science career I never had. I just followed my passion along its own meandering trajectory, always staying true to my heart (and always penniless). I travelled to deserts and rainforests and remote islands; handled hummingbirds, eagles, and flamingos; I wrote books and held exhibitions, taught people to wield a pencil and a scalpel; I studied at the Royal College of Art and worked as a curator at the Natural History Museum. It’s been an interesting journey reminiscent of G K Chesterton’s Rolling English Road: “the day we went to Cambridge by way of Mozambique”!

It was during my undergraduate years that two important things happened. 1. I chose to be swayed by my passion for natural history and not the accepted subjects for a fine art student. And 2. I began to study birds in earnest. With the low-brow object of travelling to far flung places on expeditions, I trained to become a bird ringer (a long process involving an intimate understanding of plumage and an adeptness at handling birds). And I taught myself about bird anatomy. As an artist I believe that the better you understand the inside of a subject the better you’re able to represent the surface. So I bought myself a scalpel and a pair of forceps and, beginning with a duck that I christened Amy, began what was to be many decades dismantling and re-assembling birds. I soon decided: a collection of anatomical drawings intended for artists like myself, accessible and free of the usual dry academic jargon, would be a splendid subject for a book….

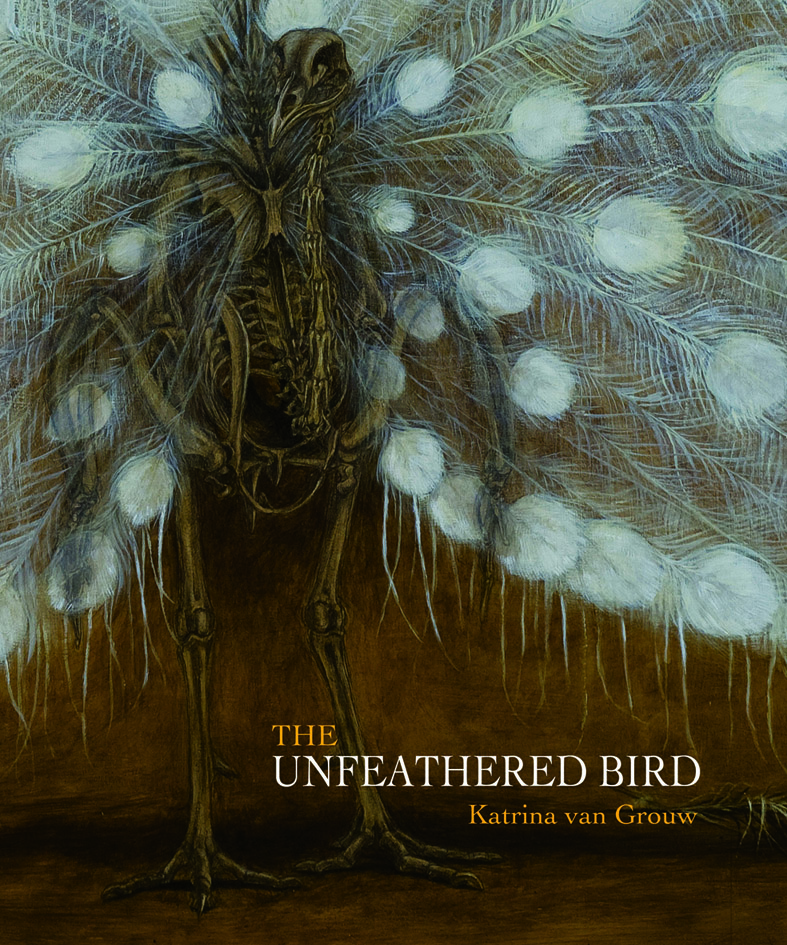

The Unfeathered Bird, 300 pages thick and lavishly illustrated, took 25 years before it was published, to tumultuous applause, in 2012. A reviewer described it as, “The best book ever to be inspired by a dead duck.” It was enjoyed by artists, birdwatchers, and professions right the way through the alphabet to vets and zoologists. But like the Ugly Duckling that eventually accepts with surprise and delight, “I AM a swan!” the swans who applauded it most resonantly and convinced me that I belonged with them, were not artists or ornithologists, but palaeontologists. Several of them are to be found in this very building.

A decade later, it was my research for the book’s much larger and more scientifically rigorous new edition—The Unfeathered Bird: Fully Fledged—that led my reading into deeper waters. Soon I was asking questions about the evolution of birds that I discovered no-one yet had answers to, and I developed a yearning to follow such questions through to wherever they might lead. Within a couple of years, and after a gruelling effort to raise the fees through a crowdfunding campaign, I joined the flock at Daniel Field’s lab here in Cambridge.

Some hours and many millions of years later, now in the light of the setting sun, the Boeing 787 was slowing for its descent over the floodplain of another river mouth, the Ashley River in the lowlands of South Carolina which has given its name to the underlying Late Oligocene Ashley River Formation. I was here in Charleston SC to, of course, study a bird.

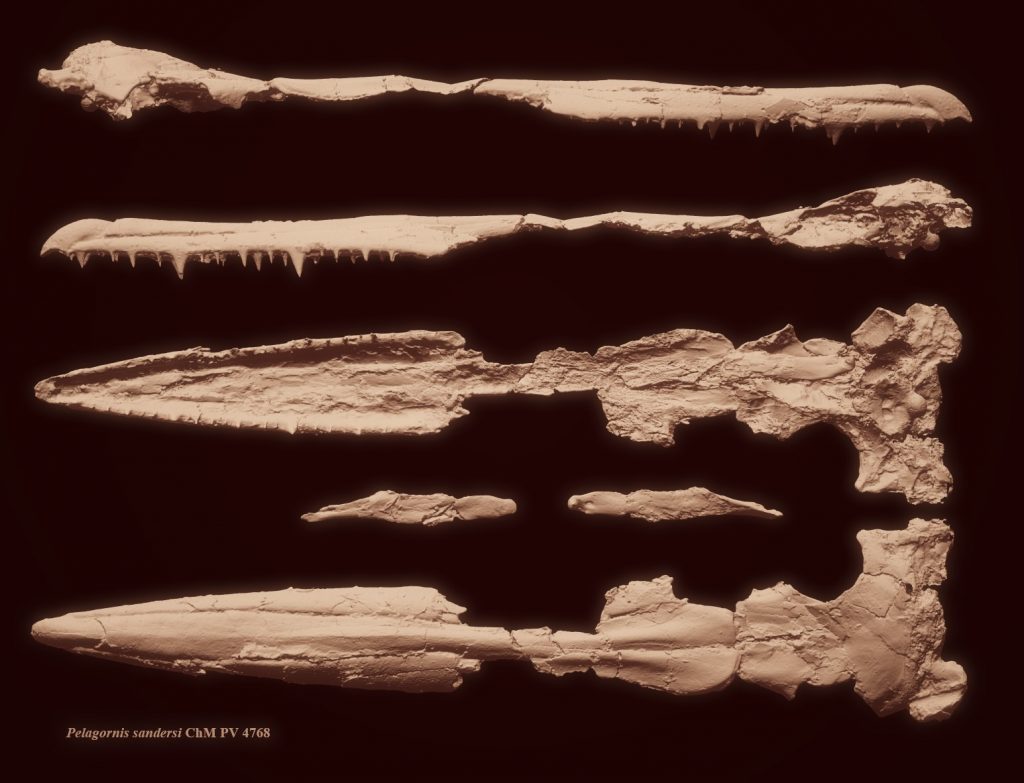

With its 7 metre wingspan Pelagornis sandersi was the largest thing in the sky; indeed quite possibly the largest flying bird to have ever lived. It would have soared effortlessly over the oceans snatching up squid or other marine invertebrates with it’s bony ‘pseudoteeth’. When it died its remains sank to the ocean floor where, 27 million years later, right here on the site of Charleston International Airport, an aerial giant of a different kind now casts its shadow.

Of all birds living and extinct, these enigmatic ocean wanderers resonate with me most. It’s a privilege to be spending the twilight years of my own journey in attempting to get to know them.

Featured image: Illustration of an Albatross © Katrina van Grouw