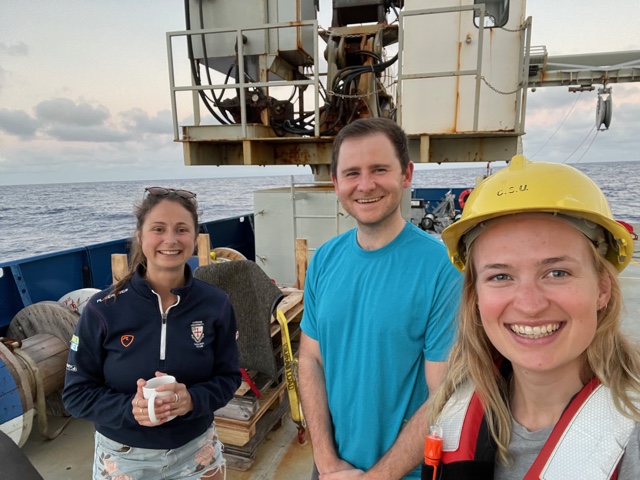

Nick Reynard is a postdoc in the Centre for Climate Repair in Cambridge, working with Ali Mashayek’s research group at the Department of Earth Sciences. Here, Nick recounts his experience of boarding a five-week scientific cruise in search of the deep Antarctic waters that rise in the Madagascar Basin.

What are we trying to understand about the ocean?

For decades, oceanographers have been going to sea to collect observational data to help us piece together how ocean water circulates and transports nutrients, heat and other tracers, such as carbon, around our planet. The sheer size of the ocean means that there remain areas where the pathways of water are still not fully known.

In April 2023, I set off on a five-week-long research cruise from Cape Town, South Africa, to Port Louis, Mauritius, aiming to find evidence of surface to deep ocean shortcuts that act on the order of decades instead of centuries.

We focused our attention on waters that originate at the surface around Antarctica, and would have sunk to the ocean floor before spreading out as they move northward in the western Indian Ocean and around Madagascar — leading to a pathway for long-term transport of tracers away from the atmosphere.

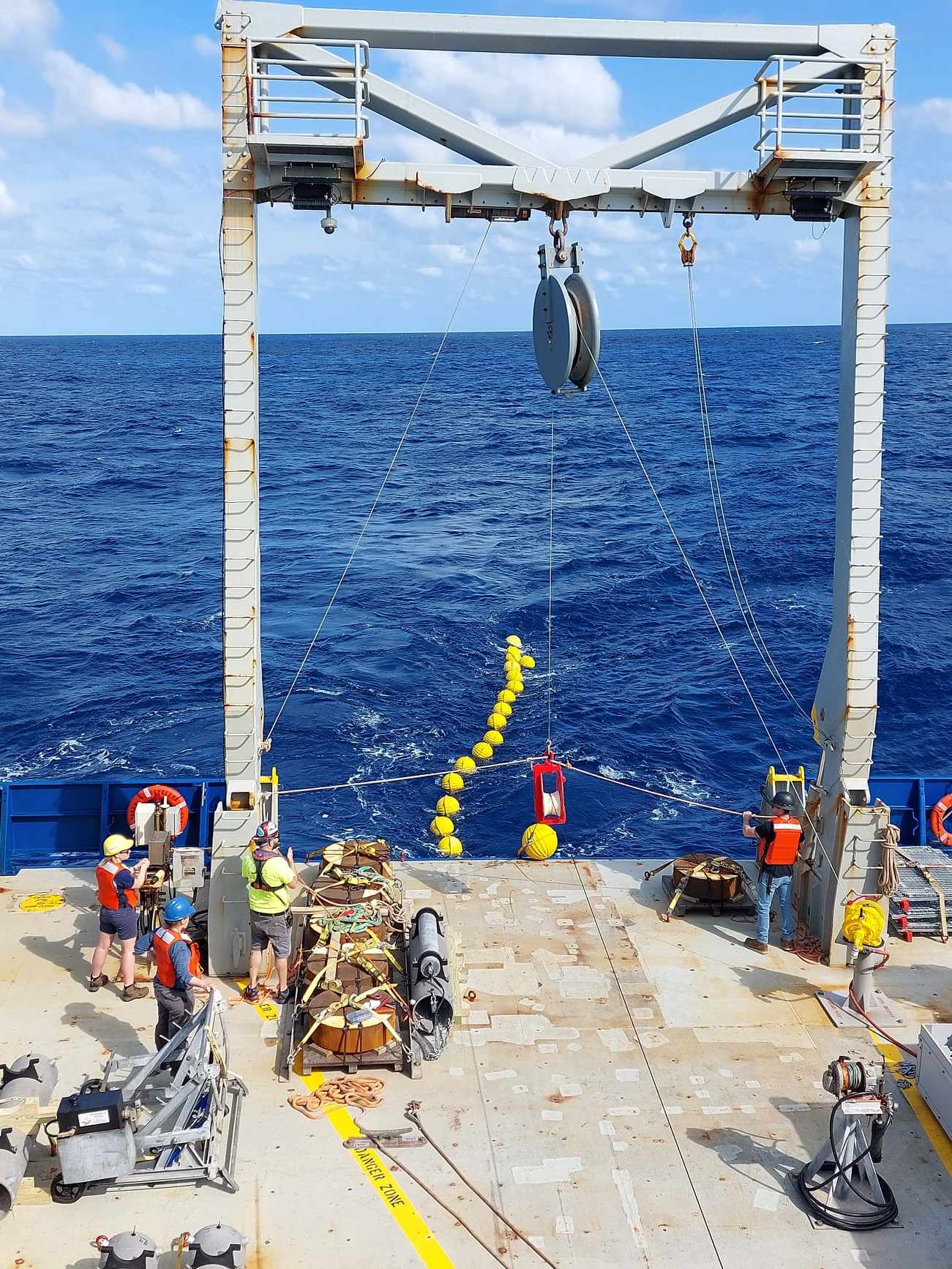

As part of this cruise we had a number of instruments to detect the presence of deep Antarctic water. These are all mounted on a circular rosette that is lowered to just 10 m above the seafloor. The deepest we went to was 5862 m.

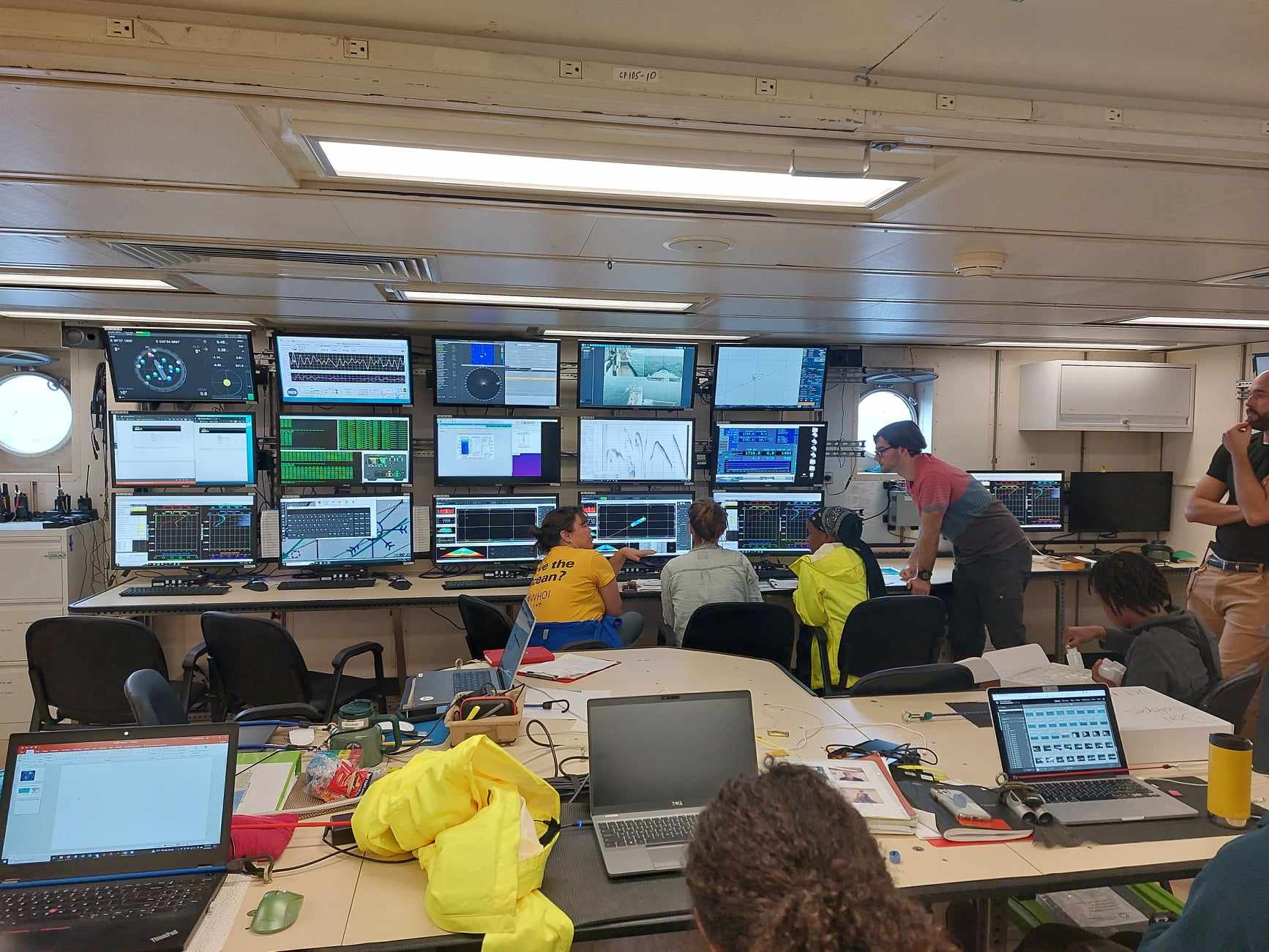

It’s common practice for cruises to attach a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature and Depth) and Niskin bottles (used to capture water samples at chosen depths) to the rosette. We also used an LADCP (Lowered Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler) to observe current speed and direction, which is the instrument that I was tasked with running for half of the day.

From the water samples collected in Niskin bottles, a number of biological or chemical properties of the water can be measured. For example, our science party looked at chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) concentration, a chemical given off by aerosols and fridges which is partly absorbed by the oceans. The release of CFCs was banned in the 1980’s, so we can use its concentration to approximate how long ago water was last in contact with the atmosphere, or the ‘age’ of the subducted water mass.

How does ocean research help us understand climate change?

Looking at the bigger picture, one reason oceanographers go to sea is to piece together how its properties have changed over time. Monitoring programs such as WOCE and GO-SHIP take measurements at the same location across multiple years to show changes to the ocean’s physical, biological and chemical properties over time.

The global ocean is a major regulator of the climate we all experience, transporting heat and carbon across the planet. Understanding how it does this is important if we want to accurately know how our planet may heat up as more emissions of greenhouse gases are released. Secondly, observational data gives a chance to validate and ground-truth complex Earth system models that are often used to inform policy makers about how best to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

What’s day-to-day life like at sea?

Five weeks on a floating steel platform in the middle of the ocean surrounded by many people you have never met could seem quite daunting at first, but onboard it quickly becomes very clear that time is going to fly by and we’ll miss it when it’s over.

This cruise was very international, with people joining from the UK, South Africa, Brazil, Madagascar, Namibia, France, Germany, Mozambique and the USA.

As soon as we seemed to get to know each other we had to effectively say goodbye to half of our shipmates as we moved on to our shift patterns. With the RV Roger Revelle being a 24-hour research ship, half of us said goodbye to a normal dinner time and set our wake-up alarms to 11.30 pm, myself included, and began working from midnight to noon while the other half of the science party worked the reverse 12-hour shift, often leaving us with just a 30 minute period to catch up! One big plus from this is the guaranteed beautiful sunrises and sunsets we’d each get to see every day.

Strangely even after 5 weeks, looking out at the ocean and the waves crashing again our ship does not get tiring. However, there were some days when the weather showed us how unforgiving it could be, as storms made their way northward from the Southern Ocean and into our path. At night we would be thrown about in our bunkbeds and during the day we would have a CTD hangar crowded with people sea-sick keeping their eye on the horizon while eating plain crackers.

Most days, however, were plain sailing; with the constant rhythmic roll of the ship adding to the fun of daily table tennis games or trying to not lose your cutlery while eating.

Leaving Cape Town we got a send-off from a harbour full of seals and even a few whales (we’re pretty sure they were southern right whales). Sea wildlife sightings included an oceanic whitetip shark, albatross, plenty of squid, flying fish, and one mahi-mahi fish that was caught and shared around for our weekly Sunday barbeque.

The cruise was part of an ongoing collaboration with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Lois Baker recently identified important deep sea interfaces in the Southern Ocean and found observational evidence of them on the Madagascar Basin cruise. You can read more about Lois’ results here.