In Part III of our blog series, we talk to Sandra Freshney, Museum Archivist, about the work she is doing to bring to light women in the Sedgwick collections.

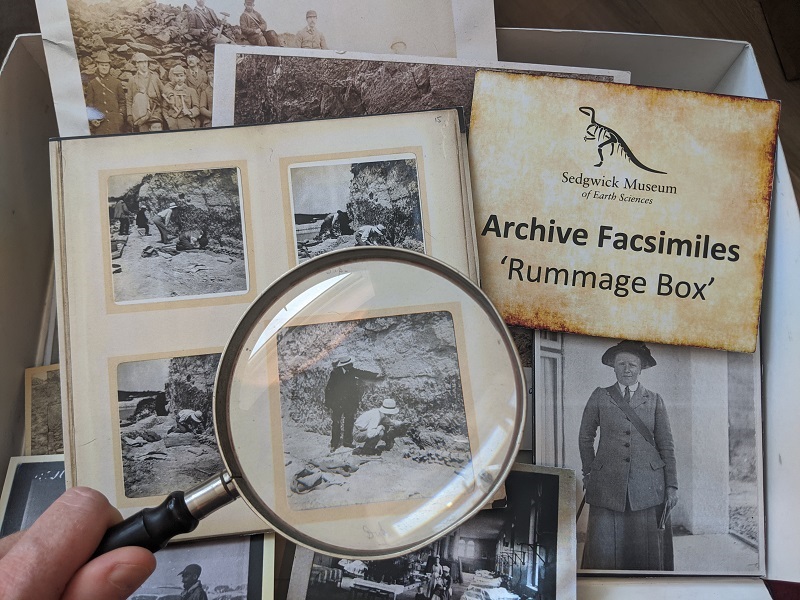

Sandra authored Women in the Archive, an online exhibition featuring documents and photos depicting the experiences of women studying geology from the 1880s until the end of the First World War. Sandra’s work challenges assumptions about what geology and geologists traditionally look like, whilst allowing quieter voices in the department’s history to be heard.

Women in the Archive

How present are women in the archives?

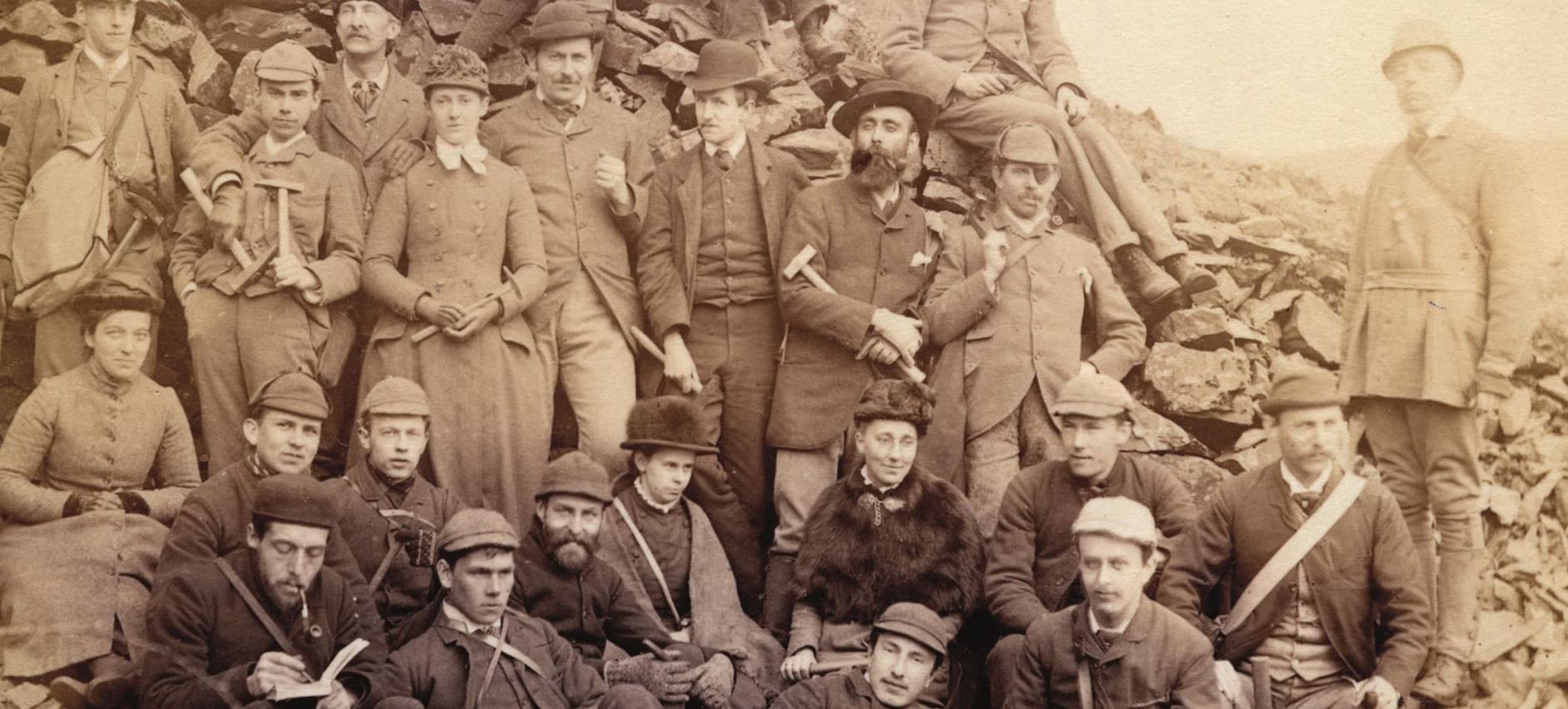

The collections are quite male dominated. The Sedgwick club is particularly interesting though because the women are so present. We may not have interviews or explicit items, but you can see them in photos and ‘hear’ them through the meeting minutes, where they presented papers.

This is the collection we’ve focussed on for this exhibition: we have the minute books of the club and have transcribed them into a spreadsheet, from which I can easily locate who was there presenting papers, what was said, who the guests were and who were honorary members and so on.

Was it difficult to select just a few items for the display?

To narrow it down, I decided to focus on the period of 1880 until World War I. Even then, there was quite a lot of content to choose from and we could have gotten carried away in the detail of the meetings that women attended, but that would have been quite a text heavy exercise. I wanted to keep a balance between text and photographs and allow for it to be a visual experience too. It was really important to have a photo of each of the women along with a summary about them. And there are many more stories we can tell in future.

Is there any sense in the archives of how the women felt about being on the expeditions with the club?

There isn’t really anything explicit about how the women felt, but it must have been unusual for that period. One of the reasons there was this change, and women became involved, goes back to the rule change that allowed Professor McKenny Hughes to marry. He married Mary, a woman who was very interested in geology and loved photography and art. Mary was very involved in the expeditions and acted as a chaperone, she was key to women being on the trips work and encouraged them to be involved. They are quite a fascinating couple – and Mary kept remarkable scrapbooks documenting some of the earlier expeditions.

Several sources give an insight into what it was like for the women. In the exhibition, I touch on an article, called ‘The Pleasure Party’ which was published in 1880 and was about a Keswick trip where Mrs Hughes was chaperone, from which I could have included many more excerpts. They talk a lot in the article about how women should appear and behave, how the weaker women ‘are not pushed beyond their powers’, ‘they’re lead with a firm hand’, ‘the professor is determined to make each girl do her best and is determined not to allow shirking, scamping, inattention, idleness in any possible form.’ There are very detailed summaries of what is going on but the article writers are very impressed with Mrs Hughes who is making sure the girls ‘behave’. From the whole piece, you can see that society is questioning what is going on.

Were there any items you wanted to include but didn’t?

Apart from the article on the Keswick trip, there is a letter, from Lydia Becker, in 1874, to Professor McKenny Hughes that I wish I had included. Lydia Becker established the Manchester Ladies Literary Society. She was quite involved in women’s suffrage, organising meetings and giving lectures. She was a pioneer of her time. Lydia wrote to McKenny Hughes thanking him for his promise of help with the Women’s Suffrage Movement. That letter is 20 years before women were allowed to become members of the Sedgwick Club so it’s interesting to see his support of that movement. I may go back to that letter as part of a future exhibition as a separate story.

We also have more to explore on later time periods for Women in the Archives Including women like Australian Geologist, Dorothy Hill, who was the first woman to be a university professor in Australia and first female president of the Australian Academy of Science; Elizabeth Caldwell, who went on to work in radar in World War II; and Kathleen Prendergast, another Australian geologist who became a doctor in the Black Watch.

Are there other voices you want to bring forward from the archives?

There’s work being done around colonialism and imperialism and enslavement. We’ve recently had a History PhD intern looking specifically at where the pieces in Woodward’s collection came from as that period is a time of enslavement. That report has just been finished. We also want to look more deeply at exchanges between museums and from country to country. There is also the collection of William McFadden, who worked in Somaliland and Iraq and that collection will be of interest.

There might not be very much but we definitely want to tease out the information that we do have. There are also stories around the students and representation. For instance, Jonathan Cutbill, who is an important LGBTQ+ figure, worked in Svalbard and he appears in that archive. There is a 1901 photo that includes a black student and we don’t know who that was yet. There’s a lot still to explore. We don’t want to out people or make assumptions but if we do know about them or we can uncover their story sensitively, if there’s something to be addressed, it’s important that we do that as the museum has a cultural role to play.

Part IV, the final in this blog series, continues to explore other perspectives and hidden stories in the Sedgwick and the Archives. Explore more online.

Keep up to date with the Sedgwick Museum on social media, by following them on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.