In June every year, the Part II examiners in Cambridge Earth Sciences select the best mapping project of the year group, based on the quality of field maps and notebooks, and on the final drafted map and report. Since 2006, this top project has won the Reekie Prize within the department; a useful accolade to put on the CV. However, a yet bigger prize is then at stake. In December, the project gets submitted for a national award: the Dave Johnston prize of the Geological Society’s Tectonic Studies Group (TSG).

For the past 20 years or more then, an A4 box file of precious project material has been delivered to the venue of the TSG annual meeting, for the scrutiny of the judges. Sometimes this file has been entrusted to the postal service. More often, it has been personally delivered by someone attending the meeting, as often as not by me. Travelling by train, transporting the bulky file meant a larger than usual rucksack, and greater than usual energy expended in lugging it around. No surprise then that I felt personally invested in the success of the Cambridge submission. And no surprise that I came home disappointed as, every year, we failed to win.

Could it be that, now I’ve retired from submission duties, a jinx has been removed? Or is it that, in these days of virtual conferences, the submission was digital not physical? Whatever, Peter Methley (Selwyn) won this year’s Dave Johnston prize for Cambridge with an impressive project on his 2019 area around Castellane, in south-east France. “We chose the area because it was relatively easy to travel to, had nice sunny weather (at least most of the time) and had interesting-looking structures on the existing geological map” Peter explains, prioritising his reasons in a time-honoured order.

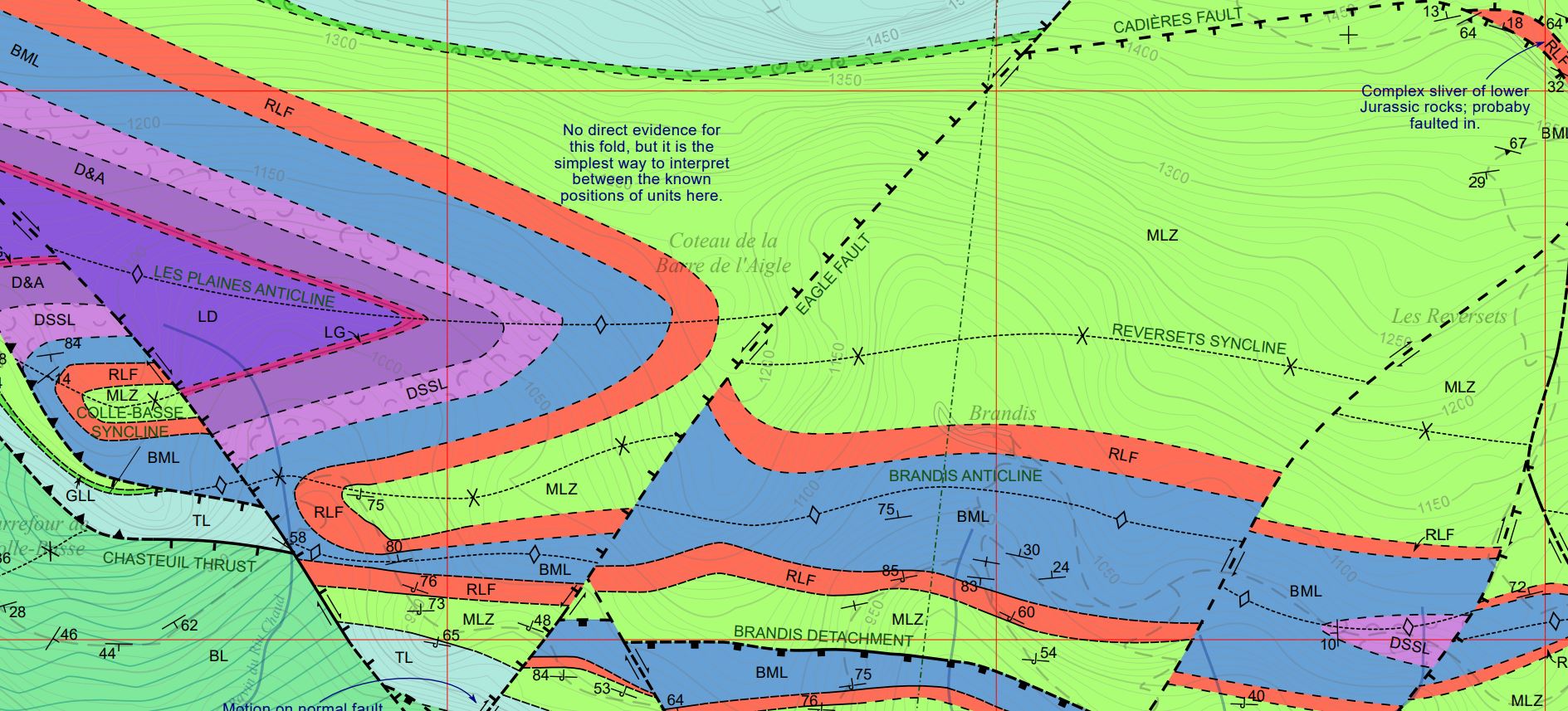

“The rock sequence tells a tale of deepening Tethys Ocean waters during the Triassic and Jurassic, followed by uplift in the Cretaceous and Palaeocene. In the Eocene and Oligocene, conglomerates, highly-fossiliferous marls, nummulitic sandstones and limestones were deposited in a foreland basin in front of the young Alps. As this was happening, north to south compression formed a series of tight folds and intricate faults in the sedimentary cover as it moved southwards over a gypsum-lubricated décollement. By the Miocene, a change in the compression direction to ENE-WSW gave the area some excellent examples of refolded folds and reactivated faults.”

The town of Castellane

View across the mapping area

The area didn’t disappoint in other ways. “The views were spectacular, although they did come with the cost of having to climb 500-metre-high mountains on a regular basis. We also had plenty of time for non-geological fun; skimming stones on the nearby lake, swimming in the rain, riding a pedalo up the Gorges du Verdon or eating our way through the local shop’s entire range of ice-cream! We even had time to go on some touristy road-trips to Cannes and Monaco (which both happen to be built on cool geology as well). Overall, mapping was a fantastic experience, and I wish I could go back there now!” says Peter with feeling, currently experiencing a Part III year done entirely under COVID restrictions.

So congratulations to Peter and to the teachers on the Sedbergh and Skye field course who taught him to map. My own delight at Peter’s win is however inevitably tinged with memories of Dave Johnston himself. Dave was a structural geology lecturer at Trinity College Dublin, who disappeared in 1995 whilst solo mapping around Annagh Head, western Ireland. Dave was probably washed off the shoreline by a freak Atlantic wave. Search parties found only his distraught dog.