Palaeontology isn’t all about adventuring into the desert to dig up rocks. Sometimes, the palaeontologists of the past managed to find so many fossil bones, they didn’t know what to do with them. These bones can lie forgotten in museum collection drawers for decades, until a PhD student comes along to study them.

Fortunately for me, some of the most commonly overlooked fossils are fragmentary, isolated bones belonging to tiny animals. As a palaeontologist who works on passerine birds, which are generally tiny (think robins and blue tits), I was very excited to go on my first museum trip to look at bird fossils. In December 2022, I visited several museums in southern Germany to poke through all the drawers that might contain some mystery bird bones.

I visited the natural history museums of Stuttgart, Karlsruhe and Munich and was absolutely overwhelmed by the number of passerine fossils in those collections; drawers containing hundreds of tiny bones! It was my first time working with fossils in real life, since most of my research is based on 3D models generated from micro-CT scans of bird skeletons.

I was most interested in the bones within the wing and the hindlimb. These bones generally preserve well and they are often complete, so they can be the easiest to compare to the bones from living birds. They are also some of the most variable bones within the passerine skeleton, and so their differing features can give us clues to which living group of passerines the fossil might be closely related to. Most of the fossil material was between 30-15 million years old from several localities in southern Germany.

I spent a very busy three weeks huddled over a microscope in the collections, finally feeling like a real palaeontologist. Many of the bones were extraordinarily small, particularly when they were just a broken piece of something. I found countless fragments of carpometacarpi (the hand bone) and tarsometatarsi (the foot bone). Some of these were so small, they must have been similar in size to the goldcrest, which is Europe’s tiniest living bird! Learning to move these fragments around was a challenge; the atmosphere was dry and static, and often bone fragments would cling to plastic.

Halfway through the trip, I met up with Daniel Field, my PhD supervisor. After some real-life passerine bird watching in Heidelberg (crested tit was one of the highlights!), we headed to Munich. In Munich we learnt that tap water is more expensive than coffee or beer, -10oC is too cold for sightseeing, and the Bavarian State Collection is a goldmine for tiny bird fossils.

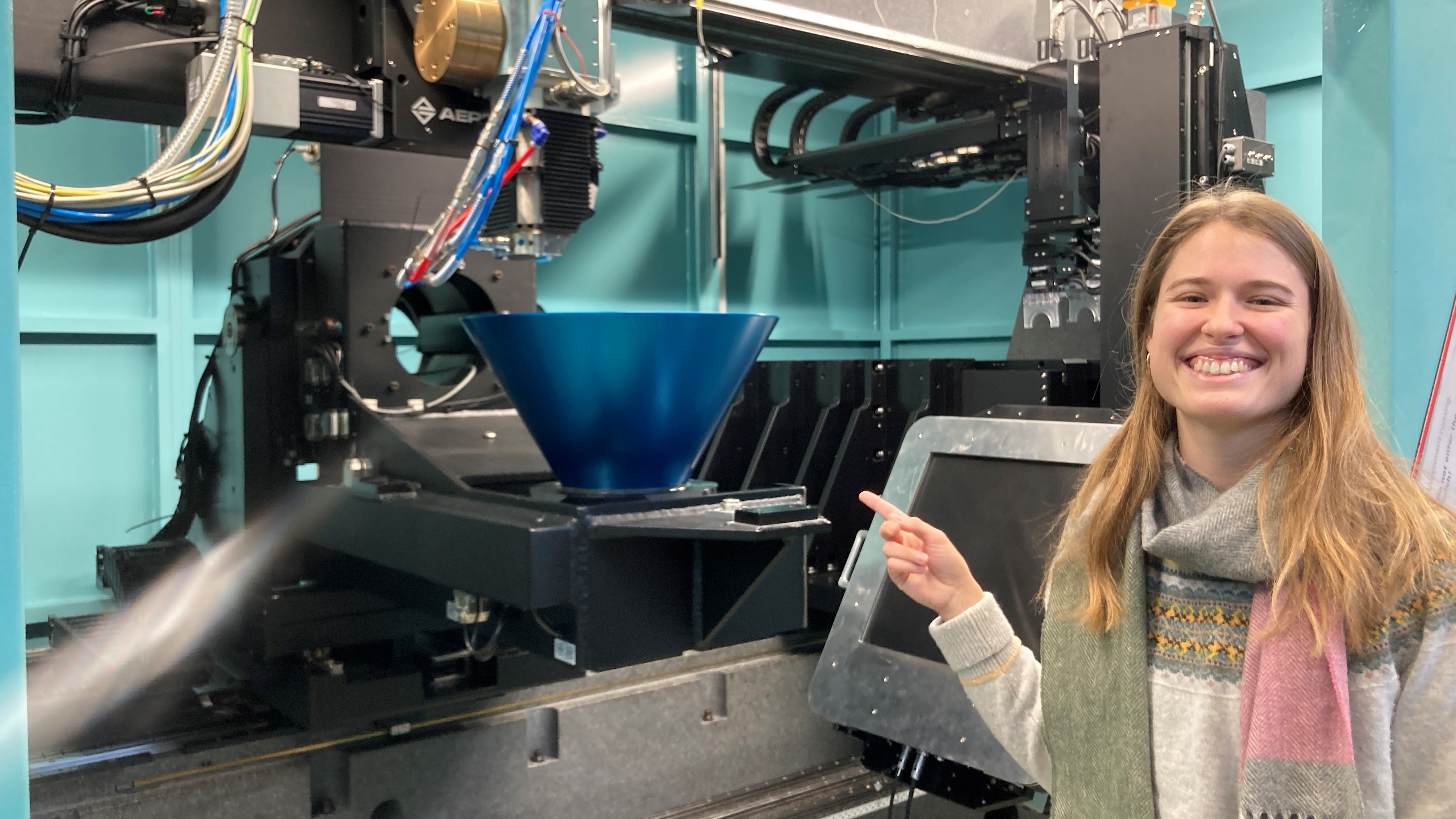

During my visit, I identified some exciting fossils that will help to unravel the evolutionary history of passerine birds. My collaborators in Germany at Stuttgart, Karlsruhe and Munich are helping to get some of these fossils micro-CT scanned at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. This institute is an amazing centre of research with state-of-the-art micro-CT scanning facilities, and visiting their giant scanner and synchrotron particle accelerator was a highlight of the trip. Many thanks to everyone who made the trip possible, including the Society of Systematic Biologists and the Natural Environment Research Council for funding my visit.