In a three-part series of blog posts, Isobel Rowell describes her experiences on the second field campaign of the WACSWAIN project. Part one outlines the motives behind the Sherman Island drilling project, and details the team’s journey to their drill site.

Introduction

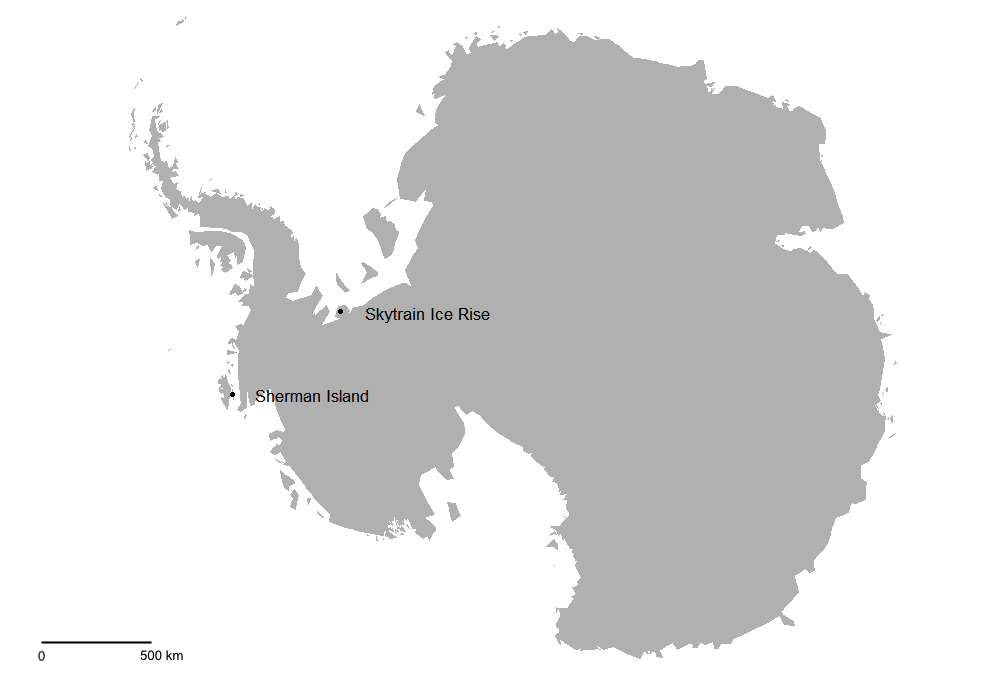

The Sherman Island Drilling Project is the second of two field campaigns under the WACSWAIN project. The result of the first field campaign—a 650 m ice core retrieved from Skytrain Ice Rise near the Ronne ice shelf—is now undergoing intense lab analysis (see Eric’s latest post), while, at the time of writing, the second field campaign is just beginning.

Ice cores may be excellent recorders of past climatic and atmospheric variables, but they only provide us with a single point measurement in space, which can only be extrapolated so far for a continent the size of Antarctica! Therefore, it is important that we collect ice from the last interglacial (LIG) from multiple sites on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) to: (i) obtain point constraints on the presence of LIG ice, and (ii) as in the case of Skytrain, determine chemical information about the region surrounding the ice core drill site. The purpose of the second field campaign on Sherman Island is to use the Rapid Access Isotope Drill (RAID) to obtain ice chippings from the surface all the way down to the bedrock. This drilling and analysis will provide a low-resolution isotope record (temperature proxy) from this part of the WAIS, and will hopefully reveal LIG ice.

Two flyovers from the IceBridge project, which scouted the Sherman Island area, revealed a ridge of ~430 m thick ice that would be suitable for our drill site. Unlike Skytrain, where LIG ice was buried under 600 m, Sherman Island is thought to have ice from the LIG (or at least the last glacial maximum) at shallower depths, due to lower accumulations rates from being in the shadow of Thurston Island. Given the high risk of not finding LIG ice before reaching bedrock, the RAID was chosen for the drilling campaign, as it could reach our target depth (collecting material along the way) faster than traditional ice core drilling techniques.

The RAID is a dry drill, so no fluid is inserted into the borehole to prevent closure, therefore drilling must be completed within a few days to avoid getting the drill trapped in the ice sheet forever. Moreover, modelling of ice movement beneath the potential drill site revealed a large uncertainty in expected rate of borehole closure, which would mean that much of the ice would need to be drilled continuously, i.e., working 24/7 until we reached the bottom or the borehole closed on us.

To Sherman Island

My fellow PhD student, Dieter, and I left Cambridge on 8th January 2020 and set off on our 9000-mile-journey to Antarctica. After flying to Punta Arenas, Chile, we boarded a British Antarctic Survey (BAS) DASH-7 aircraft, which took us to Rothera: the UK’s primary Antarctic research station. After a week of acclimatising to our stunning surroundings on the edge of Adelaide Island, training for the conditions ahead, organising cargo, and testing equipment, we were joined by the third and final member of our team: Rob Mulvaney. Just hours after Rob’s arrival, we were told that we would be leaving for Sherman Island the following day, so everyone scrambled for some last-minute packing borrowing bits of forgotten kit, and in my case, re-packing, just to be on the safe side!

To my delight, I got to be the co-pilot for our flight out of Rothera to the BAS-manned fuel depot: Fossil Bluff. From there we flew to Sky Blu, where we unloaded the aircraft and made ourselves at home. Finally, three days after leaving Rothera, we were able to fly to Sherman Island. It was a truly beautiful day, and one that will last long in my memory. We met our field guides, Sarah and Tom, who had set up a very comfortable camp for us, comprising two pyramid tents (one two-person, one three-person) and a clam tent, which would be our communal space for cooking, eating and relaxing. This small, remote wilderness of Antarctica would be our home from that moment until our work was done, and crucially, until BAS were able to send us uplift flights. As Rob, the most experienced member of our team, so delicately put it: “If the planes don’t come back, we die here.”

Continue reading Isobel’s story in Part Two.

Hi Isobel,

Do you have any photos of the erection of the sherman drill you would be happy to share.

We are using similar drill on program for AAD.

Thanks