In part two of her three-part series, Isobel Rowell describes her daily routine as part of the WACSWAIN team, drilling into the Antarctic ice sheet and sampling ice chippings from the borehole in search of ice from the last interglacial.

In case you missed it, Part One is available on the blog.

The Sherman Island RAID Drilling Campaign

In the months leading up to my Antarctica adventure, whenever I spoke to other polar scientists about my fieldwork location, I was met with grim faces. Everyone was very keen to inform me of the rough conditions that I should expect to endure in this part of Antarctica. However, for the first few days in the field, we experienced near perfect weather: barely a breath of wind and almost constant sunshine.

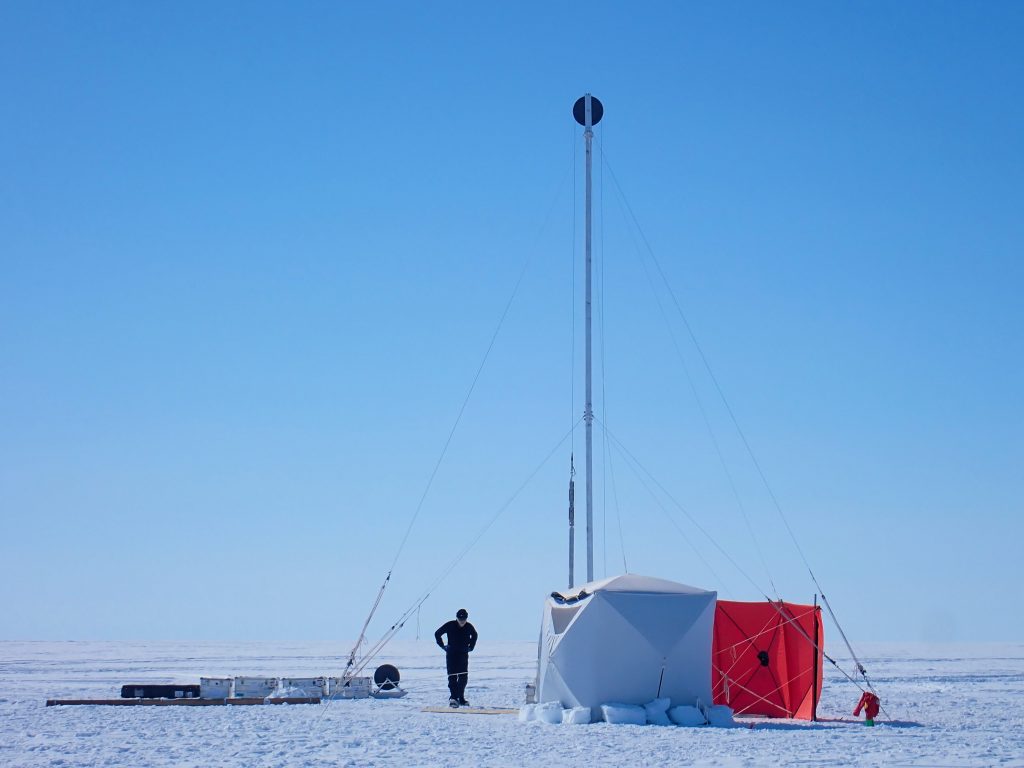

With all of our cargo on site, it was time to set up the drilling equipment. Once the winch was in place, the dead-men anchors dug in, and the 10-metre-long mast for the drill had been launched into its vertical position, the site struck an imposing figure against the vast, flat, white expanse of the ice sheet. Next came the drilling tent and wind breaks, ready for the gruelling weather that we would supposedly be fighting, not that I believed it at this stage! With everything in place, it wasn’t long before we could start drilling.

All the team watched in anticipation as the first drop of the drill was carried out—luckily all went smoothly. Rob seemed happy with the drilling parameters, and I was collecting ice samples quickly, so that the drill could descend back into the cold of the ice as soon as possible. It is crucial that the drill doesn’t get too warm at the surface, otherwise ice could melt on it’s outer casing, which could then re-freeze once the drill enters the ice and cause the drill to get lodged in the borehole. To begin with, drilling each drop only took a couple of minutes, so ice sampling at the surface had to be rapid before the next batch arrived for processing. However, as drilling progressed deeper, there was more time for sampling to take place while the drill was in the ice. Once the borehole neared the bedrock, it would take over five minutes for the drill to reach the bottom, and a further two minutes for the drilling itself, before the drill was winched out. Therefore, over time the samplers would become significantly less pressed for time, while the driller’s job would become more nerve-wracking as the risks of borehole closure increase.

The complete drilling process goes as follows:

- The empty drill is lowered into the borehole.

- The drill descends to its last recorded depth inside the borehole and stops.

- The drill begins to rotate, drilling through up to 1.5 m of solid ice, and ice chippings rise up inside the drill barrel.

- The new borehole depth is logged.

- The drill stops rotating and is winched out of the borehole.

- The drill is rotated in the opposite direction, allowing the ice chippings to fall out of the drill barrel.

- The ice chippings are funnelled into a sampling tube.

- The drill goes back to step one, while the samplers get to work.

- The samplers decide how many samples to take from the sampling tube based on how full it is (sometimes the drill goes a few centimetres under or over target).

- The samplers scoop ice out of each ‘window’ in the sampling tube, placing the ice into bags from regular intervals based on the desired resolution and to ensure that the entire depth of the tube ice is evenly sampled.

- The samples are carefully sealed. The number of samples, sampling resolution, and depth reached are recorded in an increasingly weatherworn logbook.

For the first two days of drilling, we had perfect weather and progress was good. We drilled 60–80 m each day and were in good spirits; Rob was happily drilling, and the remaining four members of the team had settled into a manageable sampling routine. Team members took it in turns to sample the ice chippings in pairs, relieving the previous pair to warm their cold hands.

When the weather finally turned, the windbreaks and shelter allowed us to continue drilling for another two days. Even though we were working in relative shelter, we had to deal with snow being blown back at us and settling on the equipment. It was quite warm, despite the winds, allowing the blown snow to melt on whatever it touched—on the sampling funnel and scoop, it was merely annoying; on our frozen fingers, it was painful. We persevered, however, and drilling continued to go well! In the evenings we did spend a little extra time in the pyramid tents to make sure that our socks and boots were dry for the following day’s work. All in all, things were going perfectly well—what could possibly go wrong?

Continue reading Isobel’s story in Part Three.

Thank you, your content is helpful and well-detailed. Looking forward to more content.